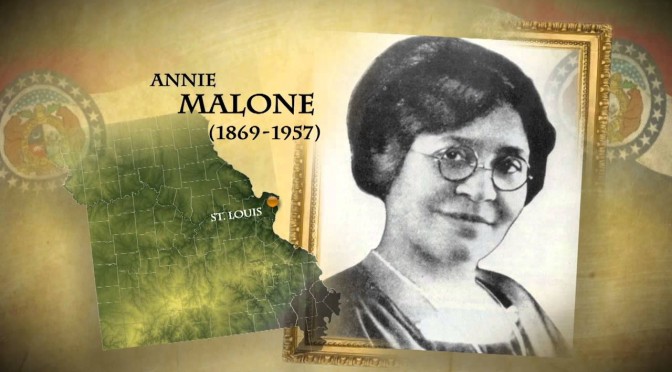

Annie Minerva Turnbo Malone (August 9, 1869 – May 10, 1957) was an American businesswoman, inventor, and philanthropist. In the first three decades of the 20th century, she founded and developed a large and prominent commercial and educational enterprise centered on cosmetics for African-American women.

Annie Minerva Turnbo was born in southern Illinois, the daughter of enslaved Africans Robert and Isabella (Cook) Turnbo. When her father went off to fight for the Union with the 1st Kentucky Cavalry in the Civil War, Isabella took the couple's children and escaped from Kentucky, a neutral border state that maintained slavery. After traveling down the Ohio River, she found refuge in Metropolis, Illinois. There Annie Turnbo was later born, the tenth of eleven children.

Annie Turnbo was born on a farm near Metropolis in Massac County, Illinois. Orphaned at a young age, Annie attended a public school in Metropolis before moving to Peoria to live with her older sister Ada Moody in 1896. There Annie attended high school, taking particular interest in chemistry. However, due to frequent illness, Annie was forced to withdraw from classes.

While out of school, Annie grew so fascinated with hair and hair care that she often practiced hairdressing with her sister. With expertise in both chemistry and hair care, Turnbo began to develop her own hair care products. At the time, many women used goose fat, heavy oils, soap, or bacon grease to straighten their curls, which damaged both scalp and hair.

By the beginning of the 1900s, Turnbo moved with her older siblings to Lovejoy, now known as Brooklyn, Illinois. While experimenting with hair and different hair care products, she developed and manufactured her own line of non-damaging hair straighteners, special oils, and hair-stimulant products for African-American women. She named her new product “Wonderful Hair Grower”. To promote her new product, Turnbo sold the Wonderful Hair Grower in bottles from door-to-door. Her products and sales began to revolutionize hair care methods for all African Americans.

In 1902, Turnbo moved to a thriving St. Louis, where she and three hired assistants sold her hair care products from door-to-door. As part of her marketing, she gave away free treatments to attract more customers.

Due to the high demand for her product in St. Louis, Turnbo opened her first shop on 2223 Market Street in 1902. She also launched a wide advertising campaign in the black press, held news conferences, toured many southern states, and recruited many women whom she trained to sell her products.

One of her selling agents, Sarah Breedlove Davis (who became known as Madam C. J. Walker when she set up her own business), operated in Denver, Colorado until a disagreement led Walker to leave the company.

This development was one of the reasons which led the then Mrs. Pope to copyright her products under the name "Poro" because of what she called fraudulent imitations and to discourage counterfeit versions. Madame C. J. Walker became one of the wealthiest African-American women in the country. Annie Malone was a millionaire before Walker, yet unlike Madame Walker, Malone lived quite modestly, so Walker is often mistakenly credited as the first black female millionaire.

In 1902 she married Nelson Pope; the couple divorced in 1907. Poro was a combination of the married names of Annie Pope and her sister Laura Roberts. Due to the growth in her business, in 1910 Turnbo moved to a larger facility on 3100 Pine Street.

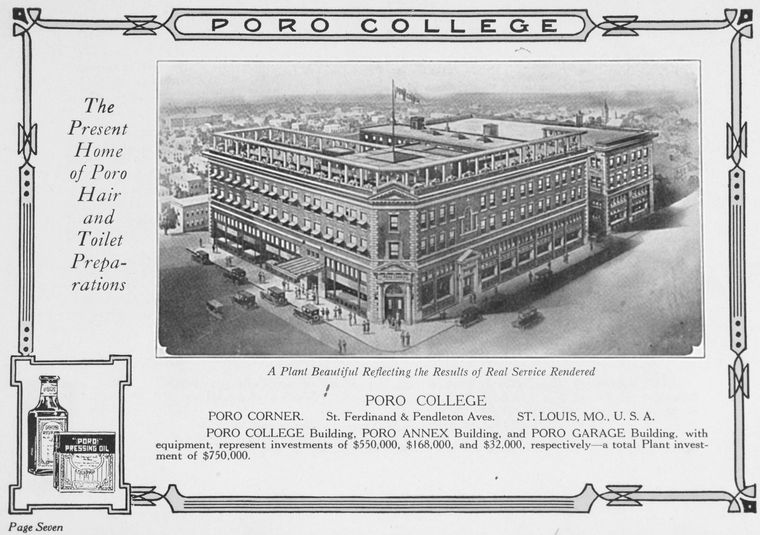

On April 28, 1914, Annie Turnbo married Aaron Eugene Malone, a former teacher, and religious book salesman. Turnbo Malone, by then worth well over a million dollars, built a five-story multipurpose facility.

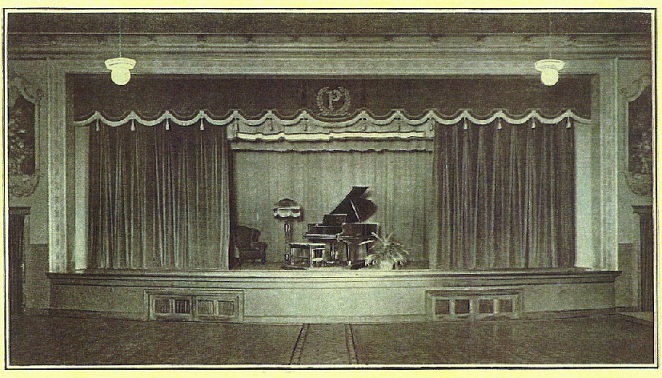

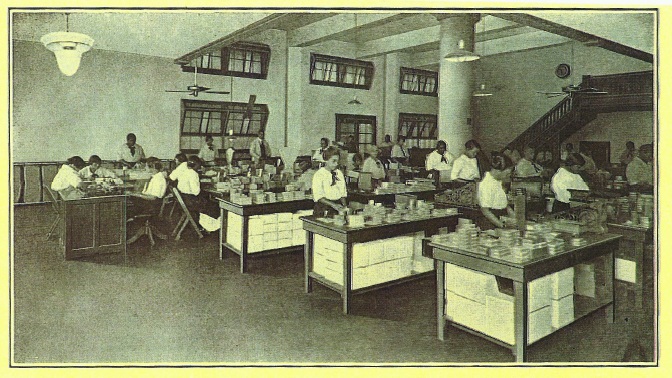

In addition to a manufacturing plant, it contained facilities for a beauty college, which she named Poro College.

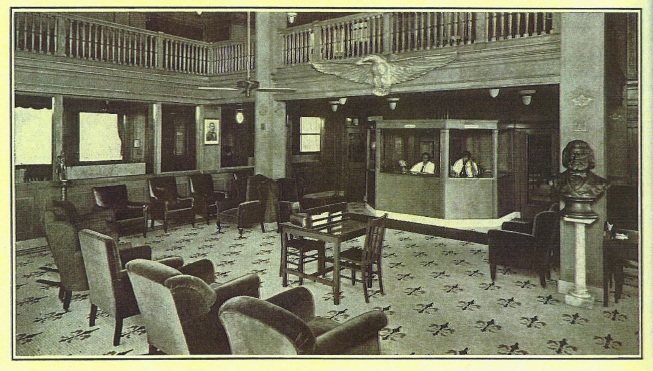

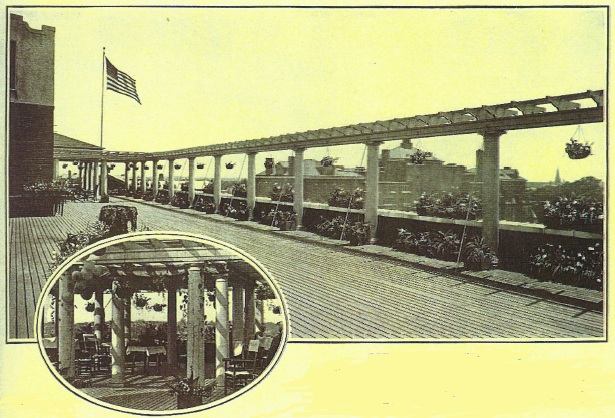

The building included a manufacturing plant, a retail store where Poro products were sold, business offices, a 500-seat auditorium, dining and meeting rooms, a roof garden, dormitory, gymnasium, bakery, and chapel.

The Poro College building served the African-American community as a center for religious and social functions.

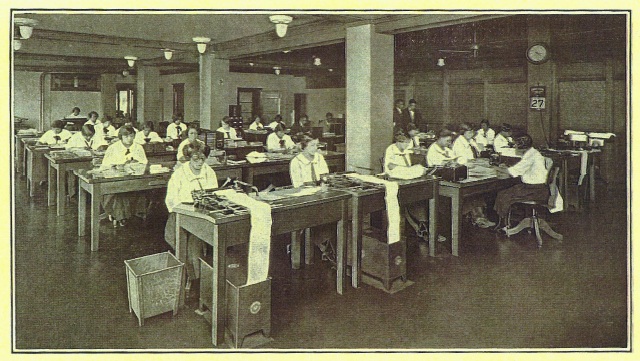

The College's curriculum addressed the whole student; students were coached on personal style for work: on walking, talking, and a style of dress designed to maintain a solid persona.

Poro College employed nearly 200 people in St. Louis. Through its school and franchise businesses, the college created jobs for almost 75,000 women in North and South America, Africa and the Philippines.

By the 1920s, Annie Turnbo Malone had become a multi-millionaire. In 1924 she paid income tax of nearly $40,000, reportedly the highest in Missouri.

While extremely wealthy, Malone lived modestly, giving thousands of dollars to the local black YMCA and the Howard University College of Medicine in Washington, DC. She also donated money to the St. Louis Colored Orphans Home, where she served as president on the board of directors from 1919 to 1943.

With her help, in 1922 the Home bought a facility at 2612 Goode Avenue (the street which was renamed Annie Malone Drive in her honor).

The Orphans Home is still located in the historic Ville neighborhood. Upgraded and expanded, the facility was renamed in the entrepreneur's honor as the Annie Malone Children and Family Service Center. As well as funding many programs, Malone ensured that her employees, all African American, were paid well and given opportunities for advancement.

Her business thrived until 1927 when her husband filed for divorce. Having served as president of the company, he demanded half of the business' value, based on his claim that his contributions had been integral to its success. The divorce suit forced Poro College into court-ordered receivership. With support from her employees and powerful figures such as Mary McLeod Bethune, she negotiated a settlement of $200,000. This affirmed her as the sole owner of Poro College, and the divorce was granted.

After the divorce, Turnbo Malone moved most of her business to Chicago’s South Parkway, where she bought an entire city block. Other lawsuits followed. In 1937, during the Great Depression, a former employee filed suit, also claiming credit for Poro's success. To raise money for the settlement, Turnbo Malone sold her St. Louis property. Although much reduced in size, her business continued to thrive.

On May 10, 1957, Annie Malone suffered a stroke and died at Chicago's Provident Hospital. Childless, she had bequeathed her business and remaining fortune to her nieces and nephews. At the time of her death, Poro beauty colleges were in operation in more than thirty U.S. cities. Her estate was valued at $100,000.

Part of the Court.rchp.com 2017 Black History Month Series

Much of the article text republished under license from Wikipedia