by William Nash, Middlebury

Was abolitionist John Brown a psychopath, a sinner or a saint?

The answer depends on whom you ask, and when.

Showtime’s “The Good Lord Bird,” based on James McBride’s novel of the same name, comes at a time when evolving popular perceptions of Brown have once again gotten people thinking and talking about him.

Since he cemented his place in history by leading a failed slave revolt at Harpers Ferry, the flinty-eyed militant’s cultural significance has waxed and waned. To some, he’s a revolutionary, a freedom fighter and a hero. To others, he’s an anarchist, a murderer and a terrorist.

My research tracks how scholars, activists and artists have used Brown and other abolitionists to comment on contemporary racial issues.

With the prominence of the Black Lives Matter movement and the president’s push for “patriotic education,” Brown is perhaps more relevant now than at any other time since the dawn of the Civil War.

So which version appears in “The Good Lord Bird”? And what does it say about Americans’ willingness to confront racial oppression?

From farmer to zealot

Born in 1800 in Torrington, Connecticut, John Brown was living a relatively undistinguished life as a farmer, sheep drover and wool merchant until the 1837 murder of abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy. An outraged Brown publicly announced his dedication to the eradication of slavery. Between 1837 and 1850 – the year of the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act – Brown served as a “conductor” on the Underground Railroad, first in Springfield, Massachusetts, and then in the Adirondacks, near the Canadian border.

Gifted a farm by wealthy abolitionist Gerrit Smith, Brown settled in North Elba, New York, where he continued helping escaped slaves and assisting the residents of Timbuctoo, a nearby community of fugitive slaves, with their subsistence farming.

In 1855, Brown took his anti-slavery fight to Kansas, where five of his sons had begun homesteading the previous year. For the Browns, the move to “Bleeding Kansas” – a territory riven by violence between pro- and anti-slavery settlers – was an opportunity to live their convictions. In 1856, pro-slavery forces sacked and burned the anti-slavery stronghold of Lawrence, Kansas. Outraged, Brown and his sons captured five settlers from three different pro-slavery families living along Pottawatomie Creek and slaughtered them with broadswords.

These brutal murders thrust Brown onto the national abolitionist stage.

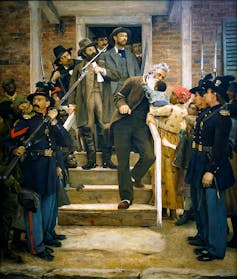

Wikimedia Commons

For the next two years, Brown led raids in Kansas and went east to raise funds to support his fights. Unbeknownst to all but a few co-conspirators, he was also planning the operation that he believed would deal slavery a death blow.

In October 1859, Brown and 21 followers raided the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia.

Brown had hoped that both Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman would join him, but neither did; perhaps their absences help explain why Brown’s expected uprising of enslaved Virginians never materialized. In addition to dooming the initial raid, the absence of a slave army torpedoed Brown’s grand plan to establish mountain bases from which to stage raids on plantations throughout the South, which he referred to as taking “the war to Africa.”

In the end, Harpers Ferry was a debacle: Ten of his band died that day, five escaped, and the remaining seven – Brown included – were tried, imprisoned and executed.

The myth of John Brown

From Pottawatomie to the present, Brown has been something of a floating signifier – a shape-shifting historical figure molded to fit the political goals of those who invoke his name.

That said, there are certain instances in which opinions coalesce.

In late October 1859, for instance, he was roundly vilified and decried as a violent madman. The outrage was so strong that five of the Secret Six – his most ardent supporters and active financial backers – denied association with Brown and condemned the raid.

profzucker/flickr, CC BY-NC-SA

But by that December, the cultural tide shifted in Brown’s favor. His jailhouse interviews and abolitionist missives, published in papers ranging from The Richmond Dispatch to the New-York Daily Tribune, galvanized admiration for Brown and amplified Northern horror over the evils of slavery. Historian David S. Reynolds deems those documents Brown’s most important contribution to the destruction of American chattel slavery.

Praised and defended by Transcendentalist writers Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, who declared the freedom fighter would “make the gallows glorious like the cross,” Brown was later described as a martyr to the anti-slavery cause. During the Civil War, Union troops sang a tribute to him as they went into battle. For many, he was the patron saint of abolitionism.

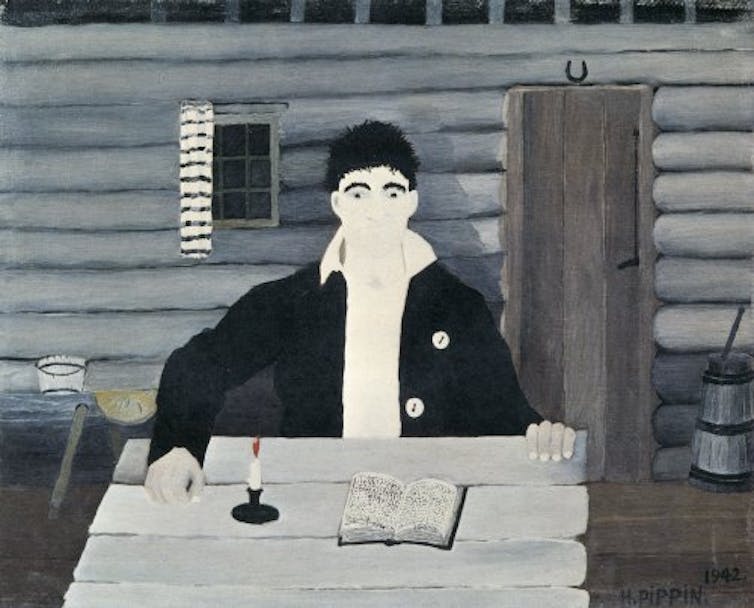

Artists, meanwhile, conjured and deployed versions of Brown in service of their work. In the 1940s, painter Jacob Lawrence created a wild-eyed firebrand Brown while Horace Pippin depicted a contemplative, sedentary Brown to showcase their divergent perspectives on Black history.

Wikiart

However, during the Jim Crow era, most white Americans – even opponents of segregation – either ignored Brown or condemned him as an anarchist and a murderer, perhaps because the delicate politics of the civil rights struggle made him too dangerous to discuss. For followers of Martin Luther King Jr.‘s philosophy of nonviolence, Brown was a figure to be feared, not admired.

In contrast, Black Americans from W.E.B. DuBois to Floyd McKissick and Malcolm X, faced with waves of seemingly endless white hostility, celebrated him for his willingness to fight and die for Black freedom.

The past three decades brought renewed interest in Brown, with no fewer than 15 books on Brown appearing, including children’s books, biographies, critical histories of Harpers Ferry, an assessment of Brown’s jailhouse months and the novels “Cloudsplitter” and “Raising Holy Hell.”

At the same time, right-wing extremists have invoked his legacy. Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh, for instance, expressed the hope that he would “be remembered as a freedom fighter akin” to Brown.

Yet Brown’s contemporary admirers also include left-wing Second Amendment advocates like the John Brown Gun Club and its offshoot, Redneck Revolt. These groups gather at events like Charlottesville’s 2017 Unite the Right March to protect liberal counterprotesters.

John Brown the … clown?

Which brings us to McBride’s novel, the inspiration for Showtime’s miniseries.

Among the most distinctive features of McBride’s novel is its bizarre humor. Americans have seen a devout John Brown, a vengeful John Brown and an inspirational John Brown. But before “The Good Lord Bird,” Americans had never seen a clownish John Brown.

McBride’s Brown is a tattered, scatterbrained and deeply religious monomaniac. In his ragged clothes, with his toes bursting out of his boots, Brown intones lengthy, discursive prayers and offers obtuse interpretations of Scripture that leave his men befuddled.

We learn all of this from Onion, the narrator, a former slave whom Brown “rescues” from one of the families living on Pottawatomie Creek. At first, all Onion wants is to get back home to his owner – a detail that speaks volumes about the novel’s twisted humor. Eventually, Onion embraces his new role as Brown’s mascot, although he continues to mock Brown’s ridiculously erratic behavior all the way to Harpers Ferry.

Like many reviewers – and apparently Ethan Hawke, who plays Brown in the Showtime series – I laughed loud and hard when I read “The Good Lord Bird.”

That said, the laughter was a bit unsettling. How and why would someone make this story funny?

At the Atlantic Festival, McBride noted that humor could open the way for “hard conversations” about America’s racial history. And Hawke’s hilarious portrayal of Brown, along with his commentary about the joys of playing this character, suggests he shares McBride’s belief that humor is a useful mechanism for fostering discussions about both slavery and contemporary race relations.

While one might reasonably say that the history of American race relations is so horrific that laughter is an inappropriate response, I think Hawke and McBride may be on to something.

One of humor’s key functions is to change people’s way of seeing, to open the possibility for a different understanding of the subject of the joke.

“The Good Lord Bird” gives readers and viewers a mechanism for seeing past the historical Brown’s violence, which is the defining feature of most iterations of him and the basis for most judgments of his character. For all of Brown’s madness, for all of his commitment to ending slavery, his care and affection for Onion show that he is fundamentally kind – an attribute that invests him with an appealing humanity more powerful than any physical blow he strikes.

Given all of the cultural baggage that John Brown has carried since Pottawatomie, giving audiences a means of empathizing with him is no mean feat.

Perhaps it will help Americans move the needle in the ongoing struggle for racial understanding – an outcome that’s as necessary now as it was in 1859. ![]()

Republished with permission under license from The Conversation.