By Cara Anthony, KFF Health News

“Get him off the table,” the doctor recalled telling the surgical team at SSM Health Saint Louis University Hospital as the team cleaned Black’s chest and abdomen. “This is my patient. Get him off the table.”

At first, no one recognized Zohny Zohny in his surgical mask. Then he told the surgical team he was the neurosurgeon assigned to Black’s case. Stunned by his orders, the team members pushed back, Zohny said, explaining that they had consent from the family to remove Black’s organs.

“I don’t care if we have consent,” Zohny recalled telling them. “I haven’t spoken to the family, and I don’t agree with this. Get him off the table.”

Black, his 22-year-old patient, had arrived at the hospital after getting shot in the head on March 24, 2019. A week later, he was taken to surgery to have his organs removed for donation — even though his heart was beating and he hadn’t been declared brain-dead, Zohny said.

Black’s sister Molly Watts said the family had doubts after agreeing to donate Black’s organs but felt unheard until the 34-year-old doctor, in his first year as a neurosurgeon, intervened.

Today, Black, now 28, is a musician and the father of three children. He still needs regular physical therapy for lingering health issues from the gun injury. And Black said he is haunted by what he remembers from those days while he was lying in a medically induced coma.

“I heard my mama yelling,” he recalled. “Everybody was there yelling my name, crying, playing my favorite songs, sending prayers up.”

He said he had tried to show everyone in his hospital room that he heard them. He recalled knocking on the side of the bed, blinking his eyes, trying to show that he was fighting for his life.

Email Sign-Up

Subscribe to KFF Health News’ free weekly newsletter, “The Week in Brief.” Your Email Address

Organ transplants save a growing number of lives in the U.S. every year, with more than 48,000 transplants performed in 2024, according to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, which oversees the nation’s transplant system. And thousands die awaiting donations that never come.

But organ donation has also faced ongoing criticism, including reports of patients showing alertness before planned organ harvesting. The results of a federal investigation into a Kentucky organ donation nonprofit, first disclosed by The New York Times in June, found that during a four-year period, medical providers had planned to harvest the organs of 73 patients despite signs of neurological activity. Those procedures ultimately didn’t take place, but federal officials vowed in July to overhaul the nation’s organ donation system.

“Our findings show that hospitals allowed the organ procurement process to begin when patients showed signs of life, and this is horrifying,” Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. said in a statement. “The entire system must be fixed to ensure that every potential donor’s life is treated with the sanctity it deserves.”

Even before this latest investigation, Black’s case showed Zohny that the organ donation system needed to improve. He was initially hesitant to talk to KFF Health News when contacted in July about Black. But Zohny said his patient’s story had stuck with him for years, highlighting that while organ donation must continue, little is understood about human consciousness. And determining when someone is dead is the critical but confusing question at play.

“There was no bad guy in this. It was a bad setup. There’s a problem in the system,” he said. “We need to look at the policies and make some adjustments to them to make sure that we’re doing organ donation for the right person at the right time in the right place, with the right specialists involved.”

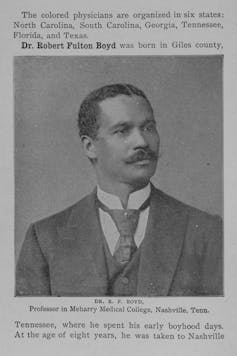

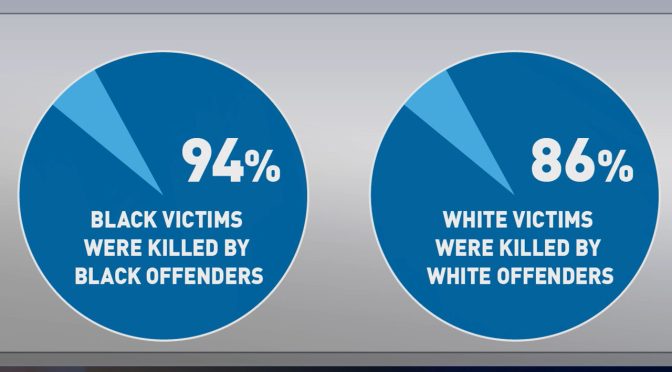

LJ Punch, a former trauma surgeon who was not involved with the case but reviewed Black’s medical records for KFF Health News, questioned whether Black’s injury — from gunfire — possibly contributed to how he was treated. Young Black men like Larry Black are disproportionately victims of gun trauma in the United States, and research on such violence is scant. His experience exemplifies “the general neglect” of Black men’s bodies, Punch said.

“That’s what comes up for me,” Punch said. “Structurally, not individually. Not any one doctor, not any one nurse, not any one team. It’s a structural reality.”

The hospital declined to comment on the details of Black’s case. SSM Health’s Kim Henrichsen, president of Saint Louis University Hospital and St. Mary’s Hospital-St. Louis, said the hospital system approaches “all situations involving critical illness or end-of-life care with deep compassion and respect.”

Mid-America Transplant, the federally designated organ procurement organization serving the St. Louis region, does not comment on individual donor cases, according to Lindsey Speir, executive vice president for organ procurement. She did tell KFF Health News that her organization has walked away from cases when patients’ conditions change — though not as late as when they are in the operating room for harvesting.

“Let me be clear about that. It happens way before then,” she said. “It definitely happens multiple times a year where we get consent. The family has made the decision, we approach, we get consent, it’s all appropriate, and then a day or so later they improve and we’re like, ‘Whoa.’”

But Speir said the recent media stories about the nation’s donation system are prompting a lot of questions about a process that also does a lot of good.

“We’re losing public trust right now,” Speir said of the industry. “And we’re going to have to regain that.”

Blink Twice for a Chance at Life

Larry Black Jr. and his sister Molly Watts are still trying to process everything that happened to him while he was hospitalized in 2019 at SSM Health Saint Louis University Hospital.

It was a Sunday afternoon when gunshots rang out in downtown St. Louis. Black had been on his way to his sister’s apartment.

“I didn’t know I was shot at first,” Black said, sitting in his living room six years later. “I literally ran like a block or two away.”

He collapsed moments later, he said, crawling to the back door of a woman’s home, where he asked for help. He said he asked the woman to give him two large towels, one covered in rubbing alcohol and another soaked with hydrogen peroxide. He wrapped those towels around the back of his head.

When his sister Macquel Payne found him, he was lying on the ground near the leasing office of her apartment complex, a crowd gathered around him.

Before an ambulance took him to the hospital, Black told his sister not to worry about him.

“I’m hearing Larry say, ‘I’m good, sis,’” Payne recalled. “‘I’m OK.’”

Black said he went in and out of consciousness on the way to the hospital and once he was there.

“I got to hitting my hand on the side of the ICU bed,” Black said. “They was like: ‘That’s just the reaction, the side effects of the medicine. Ask him some questions.’”

Payne said she asked her brother to blink twice if he could remember his first pet, a dog named “Little Black” that looked like the Chihuahua from the Taco Bell commercials.

Black said he remembers blinking twice. His sisters remember the same.

Payne asked him another question. This time she wanted to know whether her brother recognized their family. Black said he blinked twice when he saw his mom and sister standing nearby.

Black said his sister then asked him “the main question” that everyone needed him to answer.

“She’s like, ‘If you want them to pull a plug, if you tired and you giving up, blink once,’” Black recalled. “‘If you still got some fight in you, blink more than once.’”

Black said he started blinking and hit the bed to let his family know that he was still with them.

The sisters said hospital staffers told them the movements were involuntary.

‘Not Right Now’

In a waiting room steps away from the hospital’s intensive care unit, a woman carrying brochures explained to Payne and the rest of the family that Black had identified himself as a possible organ donor on his ID.

The woman wanted to know whether the family wished to move forward with the process if Black died, Payne said.

“I remember my mom saying, ‘Not right now,’” Black’s sister recalled. “‘It’s kind of too soon.’”

Payne said the woman persisted.

“She was like, ‘Well, can I at least leave you some brochures or something?’” Payne recalled. “Then my mom got a little agitated because it felt like she was being, like, pushy.”

The family was already acquainted with the organ donation process. In 2007, Black’s teenage brother Miguel Payne drowned at a local lake. His organs were donated, Macquel Payne said, noting the family was told that his body parts and tissues helped multiple people.

“I believe in saving lives,” Payne said. “But don’t be pushy about it.”

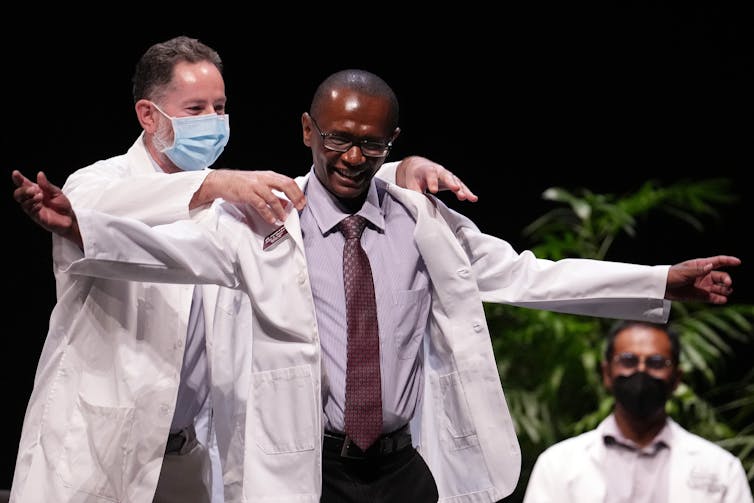

Zohny Zohny recently started a medical research company called Zeta Analytica to explore ways of quantifying consciousness, inspired in part by his experience with Larry Black Jr. in 2019. He also will be joining the West Virginia University Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute in October.

Mid-America Transplant handles the organ transplant process for 84 counties in parts of Illinois, Arkansas, and Missouri, including St. Louis. Like the Kentucky organization, it is one of 55 federally designated nonprofits that facilitate organ donations throughout the country.

The nonprofit has never pressured a family into organ donation, Speir said. Registering to be an organ donor is legally binding, she said, but Mid-America has walked away from cases when families didn’t want to move forward.

She said her staff tries to dispel myths about organ donation and alleviate concerns. “We want to have the families leave with a positive experience,” Speir said.

Despite the family’s initial ambivalence, they ultimately consented to moving forward with donating Black’s organs. Watts said members of her brother’s care team had told the family that her brother was at “the end of the road.”

The family was told to prepare for Black’s “last walk of life,” Payne said. Also known as an honor or hero’s walk, the tradition honors the life of an organ donor before the harvesting process begins.

At the time, Payne said, she thought her brother still had a fighting chance. She asked the hospital staffers to take another look at him before he was wheeled down the hall.

“I’m like, ‘My brother’s in there tapping on the bed,’” Payne said. “They said, ‘That’s just his nerves.’ But I’m like, ‘No, something’s not right.’ It’s like he was too alert. He was letting us know: ‘Please don’t let them do this to me. I’m here. I can fight this.’ They were saying that’s what the medicine will do, it affects his nerves.”

After the family had agreed to move forward with the organ donation process, the two sisters said, an especially helpful member of Black’s medical team no longer treated them the same way. She became standoffish, they said.

“You could tell the dynamics had changed,” Watts said.

‘#RIPMyBrother’

The family put on blue jumpers for the walk of life. “We just walked around the floor, and everybody was, like, acknowledging him,” Payne said. “We just thought this was the end.”

A friend Black went to high school with filmed part of the ritual. In a short clip, Black is seen being wheeled on a stretcher down a hallway in the hospital. His eyes are half-open. People are crying.

False rumors then started to swirl outside the hospital.

Macquel Payne was among the family members at SSM Health Saint Louis University Hospital when her brother Larry Black Jr. was being prepped to have his organs harvested in 2019.

Lawrence Black Sr. says he refused to believe that his son, Larry Black Jr., was dead in 2019 when he heard a rumor that his son’s body was being taken to the SSM Health Saint Louis University Hospital morgue. He says he prayed for his son to live. Today, his son is walking, talking, and the father of three children.

Brianna Floyd said she went into shock when she heard that her friend was dead. She knew that Black had been shot in the head. But a few days earlier, a local newspaper had reported that he was in stable condition.

Floyd checked Facebook to see whether the news of his death was true. Her timeline was flooded with farewell posts for Black, so she decided to write one, too.

“I Love You So Much Brother,” Floyd wrote. “#RIPMyBrother. Never Thought I Would Say That.”

Black’s father rushed to the hospital when he heard a rumor that his son was being wheeled to the morgue.

“‘He’s gone,’” Lawrence Black Sr. recalled being told. “‘He’s going to the freezer now.’”

Black Sr. said he refused to believe that his son was dead. The thought was devastating. He had already experienced that kind of loss to gun violence.

“You wake up and nothing’s the same,” Black Sr. said. “The spirit is lingering for about a week, and you can feel it, you know?”

Overwhelmed with emotion, he prayed for his son to live.

‘I Can’t Kill Your Son’

Zohny, the neurosurgeon, said he heard an announcement about a “hero’s walk” over a loudspeaker in the hospital. He wasn’t familiar with the term, so he asked about it. Medical residents in the hospital explained and told Zohny that the walk was possibly for his patient Larry Black.

“No, that can’t be my patient,” Zohny said he told them. “I didn’t agree.”

That’s when Zohny called the ICU to check on Black’s status. A person who answered the phone told him that Black was being wheeled to an operating room, he said.

“This is my first year,” Zohny said. “Your first year out as a neurosurgeon is the riskiest time for you. Any mistakes, anything small, basically derails your career. So the moment this happened, my legs went weak and I was very nervous because, at the end of the day, your job as a doctor is to be perfect.”

KFF Health News, Zohny, and Punch all reviewed the medical files given to Black from his hospitalization. It’s not clear from the records what led to that moment.

“In every case, the patient must be declared legally dead by the hospital’s medical team before organ procurement begins. This is not negotiable,” Mid-America Transplant’s CEO and president, Kevin Lee, wrote in an Aug. 21 blog post on the nonprofit’s website, responding to the news and federal comments about the investigation centered in Kentucky. “Mid-America Transplant strictly follows all laws, regulations, and hospital protocols throughout the process.”

He said in a statement to KFF Health News that a person can be pronounced dead in two ways. A person is legally dead if their heart stops beating and they stop breathing, which is when donation after cardiac death can occur. A person can also become an organ donor if their brain, including the brain stem, has irreversibly ceased functioning, which is when brain death donation can occur.

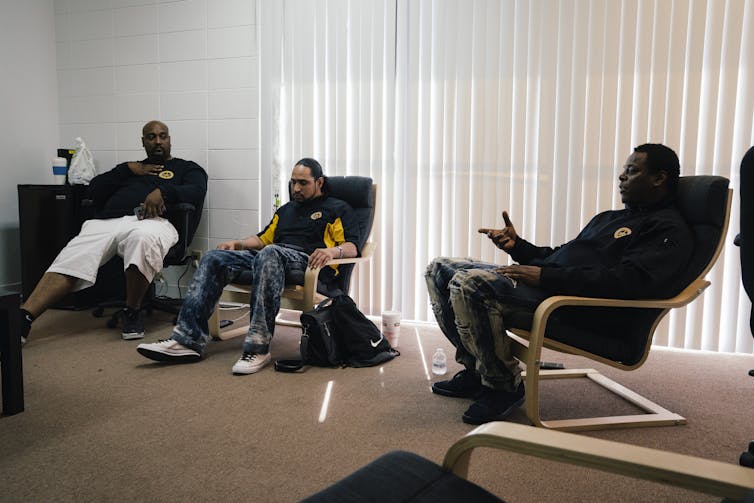

Zohny Zohny (left), a neurosurgeon, stands with his patient Larry Black Jr. and Black’s sister Molly Watts in a photograph taken at a follow-up medical appointment in 2019. Black was shot in the head in St. Louis earlier that year.

“Every hospital has their own process in declaring both types of death,” Speir said in a statement. “Mid-America Transplant ensures hospitals follow their policies.”

But Black didn’t fall into either category, Zohny said. And, he said, Black hadn’t had what is known as a brain death exam.

Zohny said he immediately informed his chairman about the situation, then started running to the operating room. Black’s family was waiting in the hallway, unaware of the drama happening behind a set of closed silver doors.

Then Zohny emerged, pulling Black’s family into an empty operating room that was nearby.

“I remember he told my mama, ‘I can’t kill your son,’” Payne recalled. “She said, ‘Excuse me?’”

Zohny put an image of Black’s brain on a screen. Then he circled the part of his brain that was damaged. He explained that Black’s gunshot wound was something that he could possibly recover from, though he might need therapy. He asked the family whether they were willing to give Black more time to heal from the injury, instead of withdrawing care.

“In my opinion, no family would ever consent to organ donation unless they were given an impression that their family member had a very poor prognosis,” Zohny said. “I never had a conversation with the family about the prognosis, because it was too early to have that discussion.”

Zohny knew that he was taking a professional risk when he ran into the operating room.

“The worst-case scenario for me is that I lose my job,” he recalled thinking. “Worst-case scenario for him, he wrongfully loses his life.”

Later, Zohny said, a hospital worker who transported Black from the ICU to the operating room told Zohny that something had seemed off.

“I remember him looking at me and saying, ‘I’m so glad you stopped that,’” Zohny recalled. “And I said, ‘Why?’ And he said: ‘I don’t know. His eyes were open the whole time, and I just felt like he was looking at me. His eyes didn’t move, but it felt like he was looking at me.’”

‘Back From the Dead’

After Zohny’s intervention, Black was wheeled back to the ICU. Zohny said the medical team held back all medications that caused his sedation.

Black woke up two days later, Zohny said, and started speaking. Within a week, the neurosurgeon said, he was standing.

“I had to learn how to walk, how to spell, read,” Black said. “I had to learn my name again, my Social, birthday, everything.”

Zohny continued to care for Black during what remained of his 21 days in the hospital. During a follow-up appointment, he posed for a photo with Black and his older sister, Watts. Next to Zohny, Black is standing up, a brace on his leg.

“It’s a miracle that despite flawed policy we were able to save his life,” Zohny said. “It was an absolute miracle.”

To help Larry Black Jr. process his gunshot injuries and an aborted surgery to harvest his organs in 2019, he makes music under the name BeamNavyLooney. “I am back from the dead,” he recently wrote in a song about his experience.

Zohny, who was working as a fellow and assistant professor at the time, left Saint Louis University Hospital for another job later that year when his fellowship ended. He said Black’s story made him question what we know about consciousness.

He’s now working on a new method that quantifies consciousness. Zohny said it could possibly be used to help measure consciousness from brain signals, such as with an electroencephalogram, or EEG, a test that measures electrical activity in the brain. Zohny said his method still needs rigorous validation, so he recently started a medical research company called Zeta Analytica, separate from his work at the West Virginia University Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute, which he’ll begin in October.

“We don’t understand the brain to the level that we should, especially with all of the technology we have now,” Zohny said.

Today, Black is trying to move forward. He said he has seizures if the bullet fragments in his head move around too much. He said he easily overheats because of the injury.

He doesn’t blame his family for their decision. But he questions the organ transplantation process. “It’s like they choose people’s destiny for them just because they have an organ donor ribbon on their ID,” Black said. “And that’s not cool.”

To help him process everything that happened to him in 2019, he makes music under the name BeamNavyLooney. “I am back from the dead,” he recently wrote in a song about his experience.

Earlier this year, Black celebrated the birth of another son, who was sleeping peacefully at home as Black recounted his story.

“He doesn’t really cry,” Black said. “He just makes noises.”

Black sat with a firearm within reach. He said he keeps the gun close to protect his family. It’s still hard for him to sleep at night. Nightmares about what happened — both on the street and in the hospital — keep him awake.

He said he no longer wants to be on the organ donor registry.

Republished with permission under license from KFF Health News.