Earlier this year, the pandemic swept across the country, killing 100,000 Americans by the spring, shuttering businesses and schools, and forcing people into their homes. It was a great time to be a debt collector.

In August, Encore Capital, the largest debt buyer in the country, announced that it had doubled its previous record for earnings in a quarter. It primarily had the CARES Act to thank: The bill delivered hundreds of billions of dollars worth of stimulus checks and bulked-up unemployment benefits to Americans, while easing pressures on them by halting foreclosures, evictions and student loan payments. There was no ban on collections of old credit card bills, Encore’s specialty.

At the same time, the pandemic compelled households to cut spending. Finding themselves with enough money to settle old debts, people responded to collectors’ calls and letters. Debt-buying executives couldn’t help marveling at their good fortune. All this created “a perfect storm from a cash perspective,” the CEO of Portfolio Recovery Associates, Encore’s main competitor, told Wall Street analysts.

After its record second quarter, analysts expect Encore to blow past $200 million in profit this year and reward stockholders with 40% earnings growth compared with last year. Portfolio Recovery is set for similar growth. The share prices of both have soared off their early April lows.

Investors didn’t even show much concern when, in early September, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau sued Encore, saying that it had broken the terms of a consent agreement struck in 2015. The agency had previously charged the company with “pressuring consumers with false statements and churning out lawsuits using robo-signed court documents,” as it said at the time. (In a statement, Encore said the CFPB’s recent suit was unnecessary because it had fixed the alleged problems “years ago.”)

In recent months, the only real bad news for debt buyers was that local courts across the country temporarily shut down. Debt collection lawsuits provide a key source of revenue for the companies, a way to extract payment from consumers, typically low-income, who don’t offer it up.

But now even that hiccup is over. After a bit of a lull in the spring, Encore and other debt buyers are back at it, filing suits by the thousands every week, according to ProPublica’s analysis of state court filings.

In August alone, Encore filed about 1,000 suits in Indiana and over 2,000 suits in the metro Atlanta area. Other debt buyers jumped back in as well. In Chicago, Portfolio Recovery filed over 3,000 suits in July, while LVNV, a major debt buyer privately owned by Sherman Financial Group, filed over 2,700 suits in Maryland in August. For all these companies, ProPublica found, the volume was well above the number they’d filed before the coronavirus arrived, in January or February of this year. No national numbers on suits exist.

In statements, the companies said they have been actively working with consumers during the COVID-19 pandemic and only sue as a last resort on a small portion of accounts.

Elizabeth A. Kersey, a spokesperson for Portfolio Recovery, said the company’s hardship program “allows for the suspension of collection efforts for ninety (90) days upon notification of a hardship event.” The company is currently not seeking new orders to seize debtors’ wages or bank account funds, she said.

Ryan Bell, an Encore executive, said, “We have consistently and proactively communicated to consumers the various relief options we’ve put in place in response to COVID-19, including temporarily stopping collections.” The company said it had stopped seeking orders to garnish bank accounts. It is, however, seizing wages.

Sherman Financial did not respond to requests for comment.

If Congress is unable to pass any further stimulus , unemployment is likely to remain high. In that scenario, debt buying companies and the banks that sell defaulted accounts to them expect more Americans to fall behind on their credit card bills over the coming months.

Even that scenario turns out to be rosy for the debt buyers. While good times can mean that Encore collects on more debt than it expected, bad times typically bring a glut of people suffering under loans they cannot repay. The result is that Encore can scoop up the raw materials for its profit machine — defaulted accounts — more cheaply. Or as Encore CEO Ashish Masih put it to Wall Street: The company is “particularly excited about the prospects for increased supply in the future.”

“The same giant debt buyers known for fighting consumer protection laws at every turn have been raking in cash during this pandemic,” Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass, told ProPublica. “They are now licking their chops in anticipation of profiting even more off families who have their hours further cut or can’t find a job, and can’t keep up with their bills or their mortgage. This is disgraceful and reinforces the need for Congress to protect consumers and small businesses from this predatory behavior.”

In recent years, Encore has bought around 2 million to 3 million U.S. accounts per year, according to public filings. Last year, on average, the company paid 8.6 cents on the dollar for each account. For a typical debt of $3,142, Encore paid $271.

To earn a profit on that investment, Encore and other debt buyers pursue debtors in near perpetuity. Encore is still collecting tens of millions of dollars each year from debts it bought in 2009 or earlier. The key to that persistence is the courts.

Since the early 2000s, debt buyers have flooded local courts nationwide with suits. The companies regularly account for more than a quarter of all debt collection cases in a given jurisdiction, according to ProPublica’s review of collection filings over several states.

That disproportionate presence has been particularly apparent in recent months, as the banks themselves have mostly opted to suspend filing new suits. In normal times, Capital One files far more lawsuits than other banks, in numbers similar to those filed by Encore and Portfolio Recovery. But since March, although Capital One continued to seize pay via garnishments secured before COVID-19 struck, it has largely stopped filing new suits.

ProPublica did find one exception among the major banks that commonly file a significant number of suits: Citigroup, which resumed filing suits at its normal levels in July. The bank, for instance, filed over 200 suits in Oklahoma in August, more than it had filed there in January and February combined.

In a statement, Citi spokesperson Jennifer Bombardier said the bank has a special assistance program for customers impacted by COVID-19 and that it is not seeking to garnish the bank accounts of customers it has sued. The bank also did not sell charged-off accounts to debt buyers “for up to 120 days” in the states “most impacted by COVID-19,” she said.

Encore sued Nicole Campbell of Brooklyn, New York, in July. Her first task was to figure out what to do. The suit was over $3,023.76 in debt she incurred years ago with CareCredit, a card offered by Synchrony Bank to people who need to cover medical costs, such as dentistry and eyecare. She knew she should answer the complaint by going to the courthouse, but she was wary of going there during the pandemic and wasn’t even sure whether it was open.

Even attorneys have difficulty finding their way. “Courts have been returning to full operation, but there’s so much confusion as to what’s happening,” said Susan Shin, legal director of the New Economy Project in New York City. “It’s hard to know what to advise people on what to do with their case.”

With help from an attorney with the New Economy Project, Campbell responded to the suit by mail. She’s not sure what to expect next but said she doesn’t have much time to worry about it. She cares for three boys, 5, 11 and 14, on her own and has to figure out how to get them to school on the city’s part-time schedule while helping them with online lessons when they’re home. She juggles this with her own job as a customer service rep: That also has a rotating, part-time schedule in order to minimize the number of people in the office.

“It’s crazy to me they’re filing all this during this time when there’s so much going on,” she said.

Such collection suits are most common among workers with income under $40,000 per year and particularly common in mostly Black neighborhoods. The suits routinely result in judgments, which in turn usually result in attempts at garnishment, according to a ProPublica analysis of Missouri court filings. Past studies have put the number of workers who have their wages garnished each year at around 4 million. In most states, plaintiffs can seize up to a quarter of a worker’s take-home pay or clean out their bank account.

In recent years, when state legislatures have moved to protect more funds from garnishment, Encore has been there to oppose the measures. In 2018, a Connecticut bill proposed to automatically protect up to $1,000 in a bank account. An Encore executive, Sonia Gibson, argued against it, writing in a letter, “Since the average amount we collect through bank garnishments is typically around $700, an automatic exemption of $1,000 would leave us unable to use bank garnishments.” The bill died.

Last year in California, Encore joined with other debt buyers to combat a similar bill that aimed to protect around $1,700.

“It was a really huge fight,” said Ted Mermin, head of the California Low-Income Consumer Coalition and a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law. “And you’ve got to think, ‘Why?’ Who on earth thinks it’s a good idea to take someone’s last dollar? The only people who would do this are debt collectors who have no ongoing relationship with someone.” The bill narrowly passed and became law.

In Washington state, lawmakers last year sought to protect more workers from wage garnishment. Under federal law, earnings above $217.50 in a week are eligible to be seized, a level that has remained the same since 2009 because it’s tied to the $7.25 federal minimum wage. The Washington bill, which ultimately passed, aimed to tie the exemption to the state’s much higher minimum wage, which this year is $13.50 an hour. In 2020, about $472.50 in weekly take-home pay would be protected. That was much too high for Encore. Gibson argued in a letter that people earning that much shouldn’t be “completely exempt from garnishment.”

As an alternative to automatic protections, Encore generally argues that consumers should have to file exemptions in court to demonstrate they really can’t afford to have their money taken. Consumer advocates say that such exemptions, which often exist in state laws, are rarely invoked by debtors because they either don’t know about them or don’t understand the process.

On paper, Randall Ward would seem to be well-insulated from garnishment. He lives in the small town of Marianna, Florida, and state law protects the wages of anyone deemed the “head of household,” which is defined as someone who earns more than half the household’s income and has dependents. Since Ward helps care for his 20-year-old son with Down syndrome and a granddaughter, his pay from his job as a manager at a Waffle House is eligible for protection.

But when Encore, after having won a judgment against Ward the previous year, sought to garnish his wages this past February, Ward didn’t understand that he qualified for the “head of household” exemption. So, starting in March, Encore began taking a quarter of Ward’s take-home pay. The size of the debt, a Citibank card that had ballooned to $5,220 with interest and court costs, meant that Ward, even with what he’s proud to call a “good job,” was in for many lean months.

The only way to make ends meet, he said, was to cancel health insurance for himself, his son and his wife, “because I could not pay the bills if I didn’t do it.”

Then the virus forced his restaurant to close for several weeks and his pay stopped altogether. The family was without income as he waited for his unemployment claim to go through. When, finally, he could go back to work, the garnishments returned. Encore has said in public statements that it looks to work with consumers, especially those who’ve been impacted by COVID-19. Ward said that was not his experience.

“They’re just ruthless about it,” he said. “I would hate to see that happen to anybody.”

Encore declined to comment on individual accounts.

Collection suits can have a lasting negative effect on consumers. A recent study by economists from Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business and the University of California, San Diego, focused on debtors who, after being sued, agreed to pay in order to avoid garnishment. The settlements left consumers worse off: They were more likely to fall behind on other debts or end up in foreclosure or bankruptcy, the study found. The main reason was that paying up on one debt had drained those consumers’ cash buffer and that left them vulnerable to falling behind on others.

Even in good economic times, low-income consumers live on the edge, so the CARES Act aid was particularly helpful to them. According to a Federal Reserve survey, the temporary $600 boost to weekly unemployment insurance benefits actually resulted in higher pay for about 40% of those who received them. On top of that came the $1,200 stimulus checks ($2,400 for married couples) with an additional $500 for each child.

In July, the Fed found households with income under $40,000 a year had significantly more savings than normal: Whereas last year just 39% said they would have covered an unexpected $400 expense with cash, this summer, 48% said they would.

Debt collectors were a clear beneficiary of those extra funds. According to a survey by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, while most people used the stimulus payments to buy food and other essentials, about 25% used at least some of the money to pay down debts.

But Felipe Severino, a Tuck School of Business professor and one of the authors of the paper on debt collection settlements, said there may be negative long-term consequences for households who used the extra money to settle older debts. The companies say they do not charge interest on the old, charged-off debts they collect so the debts are not growing.

“I would argue it’s not a very good use of their money,” he said. With less of a safety net, those households are more likely to find themselves behind on their bills again.

Furthermore, he said, stimulative government aid like the CARES Act is meant to be “spent and magnify across the economy” in the near term by, for instance, leading to increased purchases at local businesses. That doesn’t happen when the money goes to debt collectors.

The flood of government aid, along with the sudden contraction in spending due to COVID-19, has led to an unpredictable economy, one where unemployment has shot up without the usual tide of delinquencies, bankruptcies and foreclosures. But now, banks are predicting that tide to finally arrive in the coming months.

In July, Capital One reported a loss for the quarter despite delinquencies actually going down. The reason was the bank set aside $2.9 billion as a provision for future credit losses, a kind of safety net for the future.

Encore did not appear to need such precautions. “Our liquidity puts us in a strong position to capture the substantial purchasing opportunity, which we believe is sure to follow,” Masih, the CEO, told analysts.

Republished with permission under license from ProPublica.

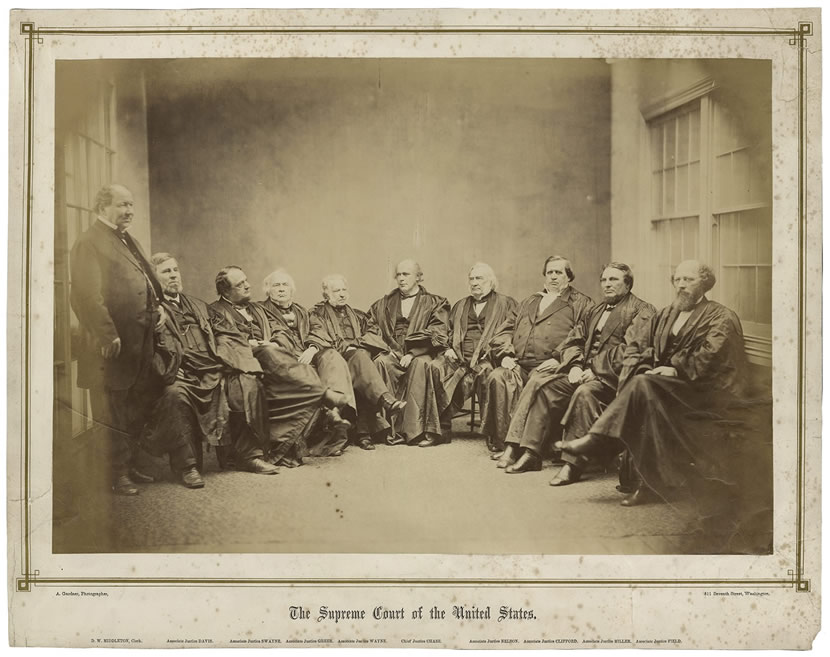

![]()