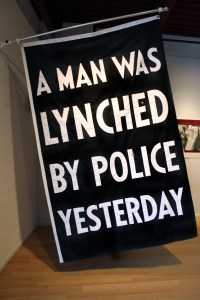

On Monday, June 20, 2016, the United States moved even closer to a police state when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Utah v. Strieff that evidence of a crime may be used against a defendant even if the police did something wrong or illegal in obtaining it. Black people have been complaining about unconstitutional searches for decades and now the Supreme Court has partially nullified fourth amendment protection for everyone against illegal searches.

The laws of the United States including federal or state statutes and local ordinance have been designed to suppress black people. There have been a number of laws specifically enacted to enslave, control movement, miseducate, and prevent the economic progress of black people. The CIA allowed drugs to be imported into black communities during the 1990s. During the Civil Rights Movement, the FBI had a secret program called COINTELPRO to discredit and disrupt civil rights leaders and protest. See U.S. Government Discrimination.

Before the United States became a country, the colonies enacted slave codes to ensure that slaves had no rights and could be treated as property. This country supposedly conceived in liberty, defined black slaves as less than human in the constitution, the Supreme Law of the United States.

Last month, I became disgusted the day I read a British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) article about how information from the CIA led to Nelson Mandela's arrest and his 27-year imprisonment in 1962. See: Nelson Mandela: CIA tip-off led to 1962 Durban arrest. Even though Nelson Mandela was president of South Africa from 1994 to 1999, he was on a US terror watch list until 2008, the same year Barack Obama was elected president. I felt a similar disgust when I learned of the Supreme Court's decision.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor, a former criminal prosecutor, dissented the US Supreme Court's decision and warned that people of color are the subject of particular scrutiny. “This court has given officers an array of instruments to probe and examine you,” she added. “When we condone officers’ use of these devices without adequate cause, we give them reason to target pedestrians in an arbitrary manner. We also risk treating members of our communities as second-class citizens.

Justice Sotomayor specifically cited the St. Louis area when she stated, "In the St. Louis metropolitan area, officers “routinely” stop people—on the street, at bus stops, or even in court—for no reason other than “an officer’s desire to check whether the subject had a municipal arrest warrant pending.”"

Justice Sotomayor's full dissent is published below.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR, with whom JUSTICE GINSBURG joins as to Parts I, II, and III, dissenting

The Court today holds that the discovery of a warrant for an unpaid parking ticket will forgive a police officer’s violation of your Fourth Amendment rights. Do not be soothed by the opinion’s technical language: This case allows the police to stop you on the street, demand your identification, and check it for outstanding traffic warrants—even if you are doing nothing wrong. If the officer discovers a warrant for a fine you forgot to pay, courts will

now excuse his illegal stop and will admit into evidence anything he happens to find by searching you after arresting you on the warrant. Because the Fourth Amendment should prohibit, not permit, such misconduct, I dissent.

I

Minutes after Edward Strieff walked out of a South Salt Lake City home, an officer stopped him, questioned him, and took his identification to run it through a police database. The officer did not suspect that Strieff had done anything wrong. Strieff just happened to be the first person to leave a house that the officer thought might contain “drug activity.” App. 16–19. As the State of Utah concedes, this stop was illegal. App. 24. The Fourth Amendment protects people from “unreasonable searches and seizures.” An officer breaches that protection when he detains a pedestrian to check his license without any evidence that the person is engaged in a crime. Delaware v. Prouse, 440 U. S. 648, 663 (1979); Terry v. Ohio, 392 U. S. 1, 21 (1968). The officer deepens the breach when he prolongs the detention just to fish further for evidence of wrongdoing. Rodriguez v. United States, 575 U. S. ___, ___–___ (2015) (slip op., at 6–7). In his search for lawbreaking, the officer in this case himself broke the law. The officer learned that Strieff had a “small traffic warrant.” App. 19. Pursuant to that warrant, he arrested Strieff and, conducting a search incident to the arrest,

discovered methamphetamine in Strieff ’s pockets. Utah charged Strieff with illegal drug possession. Before trial, Strieff argued that admitting the drugs into evidence would condone the officer’s misbehavior. The methamphetamine, he reasoned, was the product of the officer’s illegal stop. Admitting it would tell officers that unlawfully discovering even a “small traffic warrant” would give them license to search for evidence of unrelated offenses. The Utah Supreme Court unanimously agreed with Strieff. A majority of this Court now reverses.

II

It is tempting in a case like this, where illegal conduct by an officer uncovers illegal conduct by a civilian, to forgive the officer. After all, his instincts, although unconstitutional, were correct. But a basic principle lies at the heart of the Fourth Amendment: Two wrongs don’t make a right. See Weeks v. United States, 232 U. S. 383, 392 (1914). When “lawless police conduct” uncovers evidence of lawless civilian conduct, this Court has long required later criminal trials to exclude the illegally obtained evidence.Terry, 392 U. S., at 12; Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U. S.643, 655 (1961). For example, if an officer breaks into a home and finds a forged check lying around, that check may not be used to prosecute the homeowner for bank fraud. We would describe the check as “‘fruit of the poisonous tree.’” Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U. S. 471, 488 (1963). Fruit that must be cast aside includes not only evidence directly found by an illegal search but also evidence “come at by exploitation of that illegality.” Ibid. This “exclusionary rule” removes an incentive for officers to search us without proper justification. Terry, 392 U. S., at 12. It also keeps courts from being “made party to lawless invasions of the constitutional rights of citizens by permitting unhindered governmental use of the fruits of such invasions.” Id., at 13. When courts admit only lawfully obtained evidence, they encourage “those who formulate law enforcement polices, and the officers who implement them, to incorporate Fourth Amendment ideals into their value system.” Stone v. Powell, 428 U. S. 465, 492 (1976). But when courts admit illegally obtained evidence as well, they reward “manifest neglect if not an open defiance of the prohibitions of the Constitution.” Weeks, 232 U. S., at 394.Applying the exclusionary rule, the Utah Supreme Court correctly decided that Strieff ’s drugs must be excluded because the officer exploited his illegal stop to discover them. The officer found the drugs only after learning of Strieff ’s traffic violation; and he learned of Strieff ’s traffic violation only because he unlawfully stopped Strieff to check his driver’s license. The court also correctly rejected the State’s argument that the officer’s discovery of a traffic warrant unspoiled the poisonous fruit. The State analogizes finding the warrant to one of our earlier decisions, Wong Sun v. United States. There, an officer illegally arrested a person who, days later, voluntarily returned to the station to confess to committing a crime. 371 U. S., at 491. Even though the person would not have confessed “but for the illegal actions of the police,” id., at 488, we noted that the police did not exploit their illegal arrest to obtain the confession, id., at 491. Because the confession was obtained by “means sufficiently distinguishable” from the constitutional violation, we held that it could be admitted into evidence. Id., at 488, 491. The State contends that the search incident to the warrant-arrest here is similarly distinguishable from the illegal stop. But Wong Sun explains why Strieff ’s drugs must be excluded. We reasoned that a Fourth Amendment violation may not color every investigation that follows but it certainly stains the actions of officers who exploit the infraction. We distinguished evidence obtained by innocuous means from evidence obtained by exploiting misconduct after considering a variety of factors: whether a long time passed, whether there were “intervening circumstances,” and whether the purpose or flagrancy of the misconduct was “calculated” to procure the evidence. Brown v. Illinois, 422 U. S. 590, 603–604 (1975). These factors confirm that the officer in this case discovered Strieff ’s drugs by exploiting his own illegal conduct. The officer did not ask Strieff to volunteer his name only to find out, days later, that Strieff had a warrant against him. The officer illegally stopped Strieff and immediately ran a warrant check. The officer’s discovery of a warrant was not some intervening surprise that he could not have anticipated. Utah lists over 180,000 misdemeanor warrants in its database, and at the time of the arrest, Salt Lake County had a “backlog of outstanding warrants” so large that it faced the “potential for civil liability.” See Dept. of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Survey of State Criminal History Information Systems, 2014 (2015) (Systems Survey) (Table 5a), online at

https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/bjs/grants/249799.pdf

(all Internet materials as last visited June 16, 2016); Inst.for Law and Policy Planning, Salt Lake County Criminal Justice System Assessment 6.7 (2004), online at

http://www.slco.org/cjac/resources/SaltLakeCJSAfinal.pdf.

The officer’s violation was also calculated to procure evidence. His sole reason for stopping Strieff, he acknowledged, was investigative—he wanted to discover whether drug activity was going on in the house Strieff had just exited. App. 17. The warrant check, in other words, was not an “intervening circumstance” separating the stop from the search for drugs. It was part and parcel of the officer’s illegal “expedition for evidence in the hope that something might turn up.” Brown, 422 U.S., at 605. Under our precedents, because the officer found Strieff ’s drugs by exploiting his own constitutional violation, the drugs should be excluded.

III

A

The Court sees things differently. To the Court, the fact that a warrant gives an officer cause to arrest a person severs the connection between illegal policing and the resulting discovery of evidence. Ante, at 7. This is a remarkable proposition: The mere existence of a warrant not only gives an officer legal cause to arrest and search a person, it also forgives an officer who, with no knowledge of the warrant at all, unlawfully stops that person on a whim or hunch.To explain its reasoning, the Court relies on Segura v.United States, 468 U. S. 796 (1984). There, federal agents applied for a warrant to search an apartment but illegally entered the apartment to secure it before the judge issued the warrant. Id., at 800–801. After receiving the warrant, the agents then searched the apartment for drugs. Id., at

801. The question before us was what to do with the evidence the agents then discovered. We declined to suppress it because “[t]he illegal entry into petitioners’ apartment did not contribute in any way to discovery of the evidence seized under the warrant.” Id., at 815. According to the majority, Segura involves facts “similar” to this case and “suggest[s]” that a valid warrant will clean up whatever illegal conduct uncovered it. Ante, at 6–7. It is difficult to understand this interpretation. In Segura, the agents’ illegal conduct in entering the apartment had nothing to do with their procurement of a search warrant. Here, the officer’s illegal conduct in stopping Strieff was essential to his discovery of an arrest warrant.

Segura would be similar only if the agents used information they illegally obtained from the apartment to procure a search warrant or discover an arrest warrant. Precisely because that was not the case, the Court admitted the untainted evidence. 468 U. S., at 814.The majority likewise misses the point when it calls the warrant check here a “‘negligibly burdensome precautio[n]’” taken for the officer’s “safety.” Ante, at 8 (quoting Rodriguez, 575 U. S., at ___ (slip op., at 7)). Remember, the officer stopped Strieff without suspecting him of committing any crime. By his own account, the officer did not fear Strieff. Moreover, the safety rationale we discussed in Rodriguez, an opinion about highway patrols, is conspicuously absent here. A warrant check on a highway “ensur[es] that vehicles on the road are operated safely and responsibly.” Id., at ___ (slip op., at 6). We allow such checks during legal traffic stops because the legitimacy of a person’s driver’s license has a “close connection to roadway safety.” Id., at ___ (slip op., at 7). A warrant check of

a pedestrian on a sidewalk, “by contrast, is a measure aimed at ‘detect[ing] evidence of ordinary criminal wrongdoing.’” Ibid. (quoting Indianapolis v. Edmond, 531 U. S. 32, 40–41 (2000)). Surely we would not allow officers to warrant-check random joggers, dog walkers, and lemonade vendors just to ensure they pose no threat to anyone else. The majority also posits that the officer could not have exploited his illegal conduct because he did not violate the Fourth Amendment on purpose. Rather, he made “goodfaith mistakes.” Ante, at 8. Never mind that the officer’s sole purpose was to fish for evidence. The majority casts his unconstitutional actions as “negligent” and therefore incapable of being deterred by the exclusionary rule. Ibid. But the Fourth Amendment does not tolerate an officer’s

unreasonable searches and seizures just because he did not know any better. Even officers prone to negligence can learn from courts that exclude illegally obtained evidence.Stone, 428 U. S., at 492. Indeed, they are perhaps the most in need of the education, whether by the judge’s opinion, the prosecutor’s future guidance, or an updated manual on criminal procedure. If the officers are in doubt about what the law requires, exclusion gives them an “incentive to err on the side of constitutional behavior.” United States v. Johnson, 457 U. S. 537, 561 (1982).

B

Most striking about the Court’s opinion is its insistence that the event here was “isolated,” with “no indication that this unlawful stop was part of any systemic or recurrent police misconduct.” Ante, at 8–9. Respectfully, nothing about this case is isolated. Outstanding warrants are surprisingly common. When a person with a traffic ticket misses a fine payment or court appearance, a court will issue a warrant. See, e.g., Brennan Center for Justice, Criminal Justice Debt 23 (2010), online at

https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/legacy/Fees%20and%20Fines%20FINAL.pdf.

When a person on probation drinks alcohol or breaks curfew, a court will issue a warrant. See, e.g., Human Rights Watch, Profiting from Probation 1, 51 (2014), online at

https://www.hrw.org/report/2014/02/05/profiting-probation/ americas-offender-funded-probation-industry.

The States and Federal Government maintain databases with over 7.8 million outstanding warrants, the vast majority of which appear to be for minor offenses. See Systems Survey (Table 5a). Even these sources may not track the “staggering” numbers of warrants, “‘drawers and drawers’” full, that many cities issue for traffic violations and ordinance infractions. Dept. of Justice, Civil Rights Div., Investigation of the Ferguson Police Department 47, 55 (2015) (Ferguson Report), online at

https://www.justice.gov/ sites/default/files/opa/press-releases/attachments/2015/03/

04/ferguson_police_department_report.pdf.

The county in this case has had a “backlog” of such warrants. See supra, at 4. The Department of Justice recently reported that in the town of Ferguson, Missouri, with a population of 21,000, 16,000 people had outstanding warrants against them. Ferguson Report, at 6, 55. Justice Department investigations across the country have illustrated how these astounding numbers of warrants can be used by police to stop people without cause.In a single year in New Orleans, officers “made nearly 60,000 arrests, of which about 20,000 were of people with outstanding traffic or misdemeanor warrants from neighboring parishes for such infractions as unpaid tickets.” Dept. of Justice, Civil Rights Div., Investigation of the New Orleans Police Department 29 (2011), online at

https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/crt/legacy/2011/03/17/nopd_report.pdf.

In the St. Louis metropolitan area, officers “routinely” stop people—on the street, at bus stops, or even in court—for no reason other than “an officer’s desire to check whether the subject had a municipal arrest warrant pending.” Ferguson Report, at 49, 57. In Newark, New Jersey, officers stopped 52,235 pedestrians within a 4-year period and ran warrant checks on 39,308 of them. Dept. of Justice, Civil Rights Div., Investigation of the Newark Police Department 8, 19, n. 15 (2014), online at

https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/crt/legacy/2014/07/22/newark_findings_7-22-14.pdf

The Justice Department analyzed these warrant-checked stops and reported that “approximately 93% of the stops would have been considered unsupported by articulated reasonable suspicion.” Id., at 9, n. 7. I do not doubt that most officers act in “good faith” and do not set out to break the law. That does not mean these stops are “isolated instance[s] of negligence,” however. Ante, at 8. Many are the product of institutionalized training procedures. The New York City Police Department long trained officers to, in the words of a District Judge, “stop and question first, develop reasonable suspicion later.” Ligon v. New York, 925 F. Supp. 2d 478, 537–538 (SDNY), stay granted on other grounds, 736 F. 3d 118 (CA2 2013). The Utah Supreme Court described as “‘routine procedure’ or ‘common practice’” the decision of Salt Lake City police officers to run warrant checks on pedestrians they detained without reasonable suspicion. State v. Topanotes, 2003 UT 30, ¶2, 76 P. 3d 1159, 1160. In the related context of traffic stops, one widely followed police manual instructs officers looking for drugs to “run at least a warrants check on all drivers you stop. Statistically, narcotics offenders are . . . more likely to fail to appear on simple citations, such as traffic or trespass violations, leading to the issuance of bench warrants. Discovery of an outstanding warrant gives you cause for an immediate custodial arrest and search of the suspect.” C. Remsberg, Tactics for Criminal Patrol 205–206 (1995); C.Epp et al., Pulled Over 23, 33–36 (2014). The majority does not suggest what makes this case “isolated” from these and countless other examples. Nor does it offer guidance for how a defendant can prove that his arrest was the result of “widespread” misconduct. Surely it should not take a federal investigation of Salt Lake County before the Court would protect someone in Strieff ’s position.

IV

Writing only for myself, and drawing on my professional experiences, I would add that unlawful “stops” have severe consequences much greater than the inconvenience suggested by the name. This Court has given officers an array of instruments to probe and examine you. When we condone officers’ use of these devices without adequate cause, we give them reason to target pedestrians in an arbitrary manner. We also risk treating members of our communities as second-class citizens.Although many Americans have been stopped for speeding or jaywalking, few may realize how degrading a stop can be when the officer is looking for more. This Court has allowed an officer to stop you for whatever reason he wants—so long as he can point to a pretextual justification after the fact. Whren v. United States, 517 U. S. 806, 813 (1996). That justification must provide specific reasons why the officer suspected you were breaking the law, Terry, 392 U. S., at 21, but it may factor in your ethnicity, United States v. Brignoni-Ponce, 422 U. S. 873, 886–887 (1975), where you live, Adams v. Williams, 407 U. S. 143, 147 (1972), what you were wearing, United States v. Sokolow, 490 U. S. 1, 4–5 (1989), and how you behaved, Illinois v. Wardlow, 528 U. S. 119, 124–125 (2000). The officer does not even need to know which law you might have broken so long as he can later point to any possible infraction—even one that is minor, unrelated, or ambiguous. Devenpeck v. Alford, 543 U. S. 146, 154–155 (2004); Heien v. North Carolina, 574 U. S. ___ (2014). The indignity of the stop is not limited to an officer telling you that you look like a criminal. See Epp, Pulled Over, at 5. The officer may next ask for your “consent” to inspect your bag or purse without telling you that you can decline. See Florida v. Bostick, 501 U. S. 429, 438 (1991). Regardless of your answer, he may order you to stand “helpless, perhaps facing a wall with [your] hands raised.” Terry, 392 U. S., at 17. If the officer thinks you might be dangerous, he may then “frisk” you for weapons. This involves more than just a pat down. As onlookers pass by, the officer may “‘feel with sensitive fingers every portion of [your] body. A thorough search [may] be made of [your] arms and armpits, waistline and back, the groin and area about the testicles, and entire surface of the legs down to the feet.’” Id., at 17, n. 13. The officer’s control over you does not end with the stop. If the officer chooses, he may handcuff you and take you to jail for doing nothing more than speeding, jaywalking, or “driving [your] pickup truck . . . with [your] 3-year-old son and 5-year-old daughter . . . without [your] seatbelt fastened.” Atwater v. Lago Vista, 532 U. S. 318, 323–324 (2001). At the jail, he can fingerprint you, swab DNA from the inside of your mouth, and force you to “shower with a delousing agent” while you “lift [your] tongue, hold out [your] arms, turn around, and lift [your] genitals.” Florence v. Board of Chosen Freeholders of County of Burlington, 566 U. S. ___, ___–___ (2012) (slip op., at 2–3); Maryland v. King, 569 U. S. ___, ___ (2013) (slip op., at 28). Even if you are innocent, you will now join the 65 million Americans with an arrest record and experience the “civil death” of discrimination by employers, landlords, and whoever else conducts a background check. Chin, The New Civil Death, 160 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1789, 1805 (2012); see J. Jacobs, The Eternal Criminal Record 33–51 (2015); Young & Petersilia, Keeping Track, 129 Harv. L. Rev. 1318, 1341–1357 (2016). And, of course, if you fail to pay bail or appear for court, a judge will issue a warrant to render you “arrestable on sight” in the future. A. Goffman, On the Run 196 (2014). This case involves a suspicionless stop, one in which the officer initiated this chain of events without justification. As the Justice Department notes, supra, at 8, many innocent people are subjected to the humiliations of these unconstitutional searches. The white defendant in this case shows that anyone’s dignity can be violated in this manner. See M. Gottschalk, Caught 119–138 (2015). But it is no secret that people of color are disproportionate victims of this type of scrutiny. See M. Alexander, The New Jim Crow 95–136 (2010). For generations, black and brown parents have given their children “the talk”— instructing them never to run down the street; always keep your hands where they can be seen; do not even think of talking back to a stranger—all out of fear of how an officer with a gun will react to them. See, e.g., W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (1903); J. Baldwin, The Fire Next Time (1963); T. Coates, Between the World and Me (2015).

By legitimizing the conduct that produces this double consciousness, this case tells everyone, white and black, guilty and innocent, that an officer can verify your legal status at any time. It says that your body is subject to invasion while courts excuse the violation of your rights. It implies that you are not a citizen of a democracy but the subject of a carceral state, just waiting to be cataloged. We must not pretend that the countless people who are routinely targeted by police are “isolated.” They are the canaries in the coal mine whose deaths, civil and literal, warn us that no one can breathe in this atmosphere. See L. Guinier & G. Torres, The Miner’s Canary 274–283 (2002). They are the ones who recognize that unlawful police stops corrode all our civil liberties and threaten all our lives. Until their voices matter too, our justice system will continue to be anything but.

* * *

I dissent.

After Tamir’s death, the county prosecutor, Timothy McGinty, an elected official, responsible for seeking justice for Tamir, instead blamed my 12 year old boy for his own death.

After Tamir’s death, the county prosecutor, Timothy McGinty, an elected official, responsible for seeking justice for Tamir, instead blamed my 12 year old boy for his own death.