“A library outranks any other one thing a community can do to benefit its people. It is a never failing spring in the desert.” – Andrew Carnegie

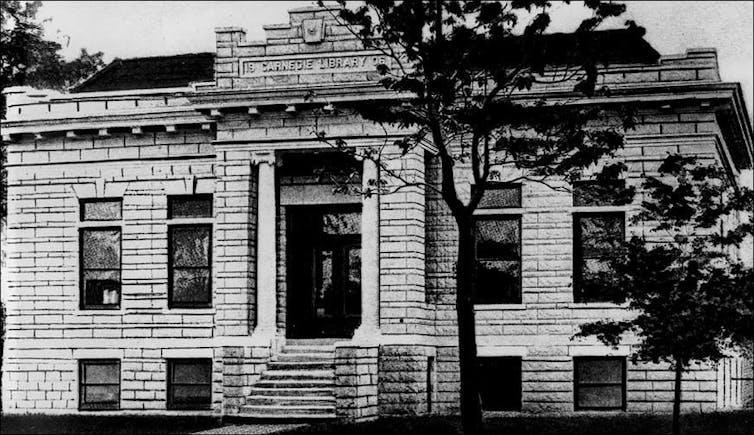

The Girard, Kansas Carnegie library. National Park Service

The Girard, Kansas Carnegie library. National Park ServiceBy Arlene Weismantel, Michigan State University

The same ethos that turned Andrew Carnegie into one of the biggest philanthropists of all time made him a fervent proponent of taxing big inheritances. As the steel magnate wrote in his seminal 1899 essay, The Gospel of Wealth:

“Of all forms of taxation this seems the wisest. By taxing estates heavily at death the State marks its condemnation of the selfish millionaire’s unworthy life.”

Carnegie argued that handing large fortunes to the next generation wasted money, as it was unlikely that descendants would match the exceptional abilities that had created the wealth into which they were born. He also surmised that dynasties harm heirs by robbing their lives of purpose and meaning.

He practiced what he preached and was still actively giving in 1911 after he had already given away 90 percent of his wealth to causes he cared passionately about, especially libraries. As a pioneer of the kind of large-scale American philanthropy now practiced by the likes of Bill Gates and George Soros, he espoused a philosophy that many of today’s billionaires who want to leave their mark through good works are still following.

The Medford, Oregon public library, depicted in this postcard, is a classic example of Carnegie library architecture. Offbeatoregon.com

A modest upbringing

The U.S. government had taxed estates for brief periods ever since the days of the Founders, but the modern estate tax took root only a few years before Carnegie died in 1919.

That was one reason why the great philanthropist counseled his fellow ultra-wealthy Americans to give as much of their money away as they could to good causes – including the one he revolutionized: public libraries. As a librarian who has held many leadership roles in Michigan, where Carnegie funded the construction of 61 libraries, I am always mindful of his legacy.

Carnegie’s modest upbringing helped inspire his philanthropy, which left its mark on America’s cities large and small. After mechanization had put his father out of work, Carnegie’s family immigrated from Dunfermline, Scotland, to the U.S. in 1848, where they settled in Allegheny, Pennsylvania.

The move ended his formal education, which had begun when he was eight years old. Carnegie, then 13, went to work as a bobbin boy in a textile factory to help pay the family’s bills. He couldn’t afford to buy books and he had no way to borrow them in a country that would have 637 public libraries only half a century later.

In 1850, Carnegie, by then working as a messenger, learned that iron manufacturer Colonel James Anderson let working boys visit his 400-volume library on Saturdays. Among those books, “the windows were opened in the walls of my dungeon through which the light of knowledge streamed in,” Carnegie wrote, explaining how the experience both thrilled him and changed his life.

Books kept him and other boys “clear of low fellowship and bad habits,” Carnegie said later. He called that library the source of his largely informal education.

Carnegie eventually built a monument to honor Anderson. The inscription credits Anderson with founding free libraries in western Pennsylvania and opening “the precious treasures of knowledge and imagination through which youth may ascend.”

This postage stamp depicted the steelmaker in a library, halfway through a book.

Supporting communities

Carnegie believed in exercising discretion and care with charitable largess. People who became too dependent on handouts were unwilling to improve their lot in life and didn’t deserve them, in his opinion. Instead, he sought to “use wealth so as to be really beneficial to the community.”

For the industrial titan, that meant supporting the institutions that empower people to pull themselves up by their bootstraps like universities, hospitals and, above all, libraries.

In Carnegie’s view, “the main consideration should be to help those who will help themselves.” Free libraries were, in Carnegie’s opinion, among the best ways to lend a hand to anyone who deserved it.

Carnegie built 2,509 libraries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, 1,679 of them across the U.S. in nearly every state. All told, he spent US$55 million of his wealth on libraries. Adjusted for inflation, that would top $1.3 billion today.

Some were grand but about 70 percent of these libraries served towns of less than 10,000 and cost less than $25,000 (at that time) to build.

A lasting legacy

Through Carnegie’s philanthropy, libraries became pillars of civic life and the nation’s educational system.

More than 770 of the original Carnegie libraries still function as public libraries today and others are landmarks housing museums or serving other public functions. More importantly, the notion that libraries should provide everyone with the opportunity to freely educate and improve themselves is widespread.

I believe that Carnegie would be impressed with how libraries have adapted to carry out his cherished mission of helping people rise by making computers available to those without them, hosting job fairs and offering resume assistance among other services.

Public libraries in Michigan, for example, host small business resource centers, hold seminars and provide resources for anyone interested in starting their own businesses. The statewide Michigan eLibrary reinforces this assistance through its online offerings.

The Michigan eLibrary, however, gets federal funding through the Institute of Museum and Library Services. And the Trump administration has tried to gut this spending on local libraries. Given Carnegie’s passions, he surely would have opposed those cuts, along with the bid by President Donald Trump and Republican lawmakers to get rid of the estate tax.

George Soros, right, eyed the busts of Andrew Carnegie on a mantel, as he sat with the late David Rockefeller in 2001 when they were among the first recipients of the Carnegie Medals of Philanthropy. AP Photo/Richard Drew

Outside of government, Carnegie’s ideas about philanthropy are still making a difference. In the Giving Pledge, contemporary billionaires, including Bill and Melinda Gates and Warren Buffett, have promised to give away at least half of their wealth during their lifetimes to benefit the greater good instead of leaving it to their heirs.

Following in Carnegie’s footsteps, the Gates family has supported internet access for libraries in low-income communities and libraries located abroad. Several billionaires, including Buffett, have publicly professed their support for the estate tax. A philosophy of giving and public responsibility may be one of Carnegie’s most enduring legacies.

![]() Editor’s Note: The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is a strategic partner of The Conversation US and provides funding for The Conversation internationally as does the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Editor’s Note: The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is a strategic partner of The Conversation US and provides funding for The Conversation internationally as does the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Article republished with permission under license from The Conversation. Read the original article.