Behzad Mirhashem, University of New Hampshire

What the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution means when it protects citizens against an unreasonable search by government agents isn’t entirely clear. It certainly includes police physically entering a person’s home, but for almost 100 years, the Supreme Court has tried to define what else might qualify, including keeping the law up-to-date with new technologies – as a recent case illustrates.

In that case, the FBI used cellphone records to show that a crime suspect’s mobile phone had been near the location of several robberies. The agency had gotten those records, without a warrant, from the company that provided the suspect with mobile service. The suspect argued that because the records were so invasive of his privacy – by revealing his physical locations over a period of time – obtaining them should be considered a search under the Constitution, and therefore require a warrant. The Supreme Court agreed.

To someone like me, who teaches law students about the relationship between the Constitution and police investigations, this case is another milestone in the back-and-forth between the police and the citizenry over technology and privacy.

An early wiretapping case

As technology has developed, police have found new ways of collecting incriminating information without trespassing onto the suspect’s property. A century ago, police were beginning to tap phone lines to listen in on suspects’ conversations. In 1928, the Supreme Court ruled that wiretaps didn’t need warrants, so long as police didn’t enter the target’s own property to install the wires. The Supreme Court said the Fourth Amendment was concerned only with protecting material things, such as a person’s home or papers.

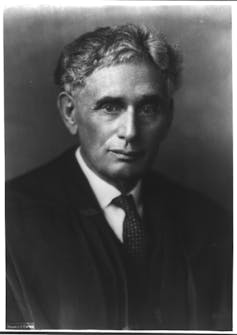

The decision came with a notable dissent from Justice Louis Brandeis, who argued that police listening in on phone conversations was indeed a search, because the Constitution’s authors meant to protect more than just tangible property:

“They sought to protect Americans in their beliefs, their thoughts, their emotions and their sensations. They conferred, as against the government, the right to be let alone – the most comprehensive of rights and the right most valued by civilized men.”

Expectation of privacy and the risk of sharing information

In 1967, the Supreme Court decided that Brandeis was right after all. Limiting the Fourth Amendment to material searches left too much of modern life completely outside the protections of the Constitution. Explaining that the Fourth Amendment protects people, not places, the justices ruled that police tapping into a private phone conversation – in that case by attaching a listening device to the outside of a public telephone booth – was a search.

In its decision, the Supreme Court created a new way of thinking about what is a search: As long as an individual is seeking to preserve something as private, and his expectation of privacy is one that society as a whole recognizes as reasonable, then official intrusion is a search. For example, when a person steps into a phone booth and closes the door, he is seeking to have a private conversation, and reasonably expects that the call will remain private from those outside the phone booth. Therefore, tapping into that call is a search.

But in the 1970s and 1980s, the Supreme Court narrowed the protection, for instance declaring that police didn’t need a warrant to find out what number the person called. The logic went that the caller voluntarily shared the recipient’s number with the phone company, and therefore willingly took the risk that it might be shared with police.

Privacy protections reemerge

In the past two decades, though, the Supreme Court has expanded Fourth Amendment protections against police searches. In 2001, the Supreme Court concluded that police needed to get a warrant before using a thermal imager to spot a marijuana growing operation inside a house. In 2012, the justices ruled officers needed a warrant before placing a GPS tracker on a suspect’s car. Add to these the most recent decision, that obtaining a person’s historical cell tower location data also requires a warrant.

The justices – like society as a whole – are increasingly recognizing that new technologies, especially digital ones, pose growing privacy challenges. For example, the Supreme Court said a few years ago that, while police could still search a person after their arrest without a warrant, they needed one to search the data on the arrested person’s cellphone.

In its most recent decision, the Supreme Court noted that cell service providers save cell tower data for five years. That kind of information can reveal a huge amount about a person’s private life, especially when coupled with additional information that may be publicly available.

Smartphones have become an integral part of modern life over the past decade – and using one inherently involves sharing location data with the cell company. The justices have realized that regular people aren’t willing to accept the risk that participating in modern society means police could discover their movements over the previous five years without even getting a warrant.

A potential new rationale

The justices are also increasingly focused on the Fourth Amendment’s language and history. The Fourth Amendment says nothing about privacy as such, but establishes the “right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers and effects.”

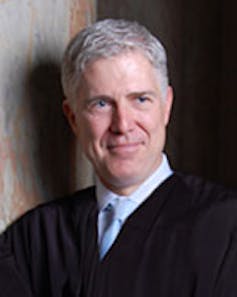

In the cell tower case, the newest justice, Neil Gorsuch, dissented from the privacy reasoning of the majority’s decision, saying courts should stick more closely to the original text of the Fourth Amendment. But he then went on to say that the Supreme Court could interpret “papers and effects” to include digital information.![]() It remains to be seen whether the Supreme Court will extend Fourth Amendment protections to emails stored on Gmail or Microsoft servers, or to password-protected websites people use to share photos with family and friends. As digital technology evolves and integrates into people’s lives in new ways, the Supreme Court will continue to wrestle with how to interpret the static text of the Fourth Amendment, adopted in 1791, in the 21st century.

It remains to be seen whether the Supreme Court will extend Fourth Amendment protections to emails stored on Gmail or Microsoft servers, or to password-protected websites people use to share photos with family and friends. As digital technology evolves and integrates into people’s lives in new ways, the Supreme Court will continue to wrestle with how to interpret the static text of the Fourth Amendment, adopted in 1791, in the 21st century.

Republished with permission under license from The Conversation.

Behzad Mirhashem, Associate Professor of Law and Director of Criminal Practice Clinic, University of New Hampshire

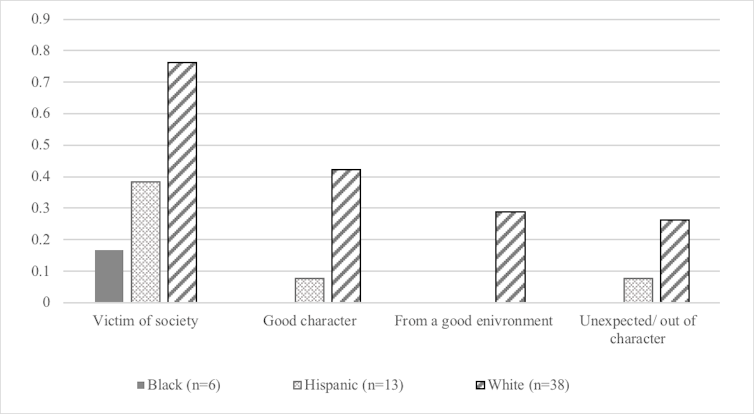

This isn’t to say that crimes shouldn’t be fully examined and that personal hardships and society don’t play a role. But if the circumstances of one group’s crimes are being explained in an empathetic way, and another group’s crimes aren’t given the same level of care and attention, we wonder whether this can insidiously influence how we perceive huge swaths of the population – criminal or not.

This isn’t to say that crimes shouldn’t be fully examined and that personal hardships and society don’t play a role. But if the circumstances of one group’s crimes are being explained in an empathetic way, and another group’s crimes aren’t given the same level of care and attention, we wonder whether this can insidiously influence how we perceive huge swaths of the population – criminal or not.