As a candidate last year, Donald Trump promised retribution against his perceived enemies. As president, he is doing that.

At the Department of Justice, a “Weaponization Working Group” has a long list of Trump’s perceived enemies to investigate. At the FBI, director Kash Patel has conducted a political purge, firing the highest officials at the bureau and thousands of FBI agents who investigated alleged crimes by Trump as well as investigated participants in the Jan. 6, 2021, U.S. Capitol riots.

It marks the first time since J. Edgar Hoover’s 48-year reign as FBI director that the FBI has targeted massive numbers of people perceived to be political enemies.

Trump’s recent fury showed how much he expects top officials in federal law enforcement to carry out his retribution.

He was enraged when Erik S. Siebert, the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia, decided there was insufficient evidence to charge two people Trump regards as enemies: former FBI director James Comey and New York Attorney General Letitia James.

“I want him out,” Trump angrily told reporters on Sept. 19, 2025. Siebert resigned, although Trump claimed he had fired him.

Trump’s most recent demands for retribution came soon after top adviser Stephen Miller’s vow to prosecute leftists in the “vast domestic terror movement” – that the administration blames, without evidence, for Charlie Kirk’s assassination – using “every resource we have.”

As the director of the FBI, Patel will likely be in charge of the investigations of perceived enemies generated by the Department of Justice and the White House. He already has sacrificed the bureau’s independence, making it essentially an arm of the White House.

This isn’t the first time an FBI director has been driven by a desire to suppress the rights of people perceived to be political enemies. Hoover, director until his death in 1972, operated a secret FBI within the FBI that he used to destroy people and organizations whose political opinions he opposed.

A burglary’s revelations

Hoover’s secret FBI was revealed, beginning in 1971, when a group of people called the Citizens Commission to Investigate the FBI broke into an FBI office and removed files.

This group suspected Hoover’s FBI was illegally suppressing dissent. Given Hoover’s enormous power, they thought it was unlikely any government agency would investigate the FBI. They decided documentary evidence was needed to convince the public that suppression of dissent – what they considered a crime against democracy – was taking place.

In my book “The Burglary: The Discovery of J. Edgar Hoover’s Secret FBI,” I describe how these eight people decided to risk imprisonment and break into the FBI’s office in Media, Pennsylvania.

The files they stole and made public confirmed the FBI was suppressing dissent. But they revealed much more: Hoover’s secret FBI and the startling crimes he had committed. These secret operations had become so extensive that they eventually diminished the bureau’s capacity to carry out its core mission: law enforcement.

Hoover, one of the most admired and powerful officials in the country, had secretly conducted a wide array of operations directed against people whose political opinions he opposed.

The files revealed that agents were instructed to “enhance paranoia” and make activists think there was an FBI agent “behind every mailbox.” Questioning Vietnam war policy could cause anyone, even a U.S. senator, Democrat J. William Fulbright of Arkansas, to be placed under FBI surveillance.

It was the revelation of Hoover’s worst operations, COINTELPRO – what Hoover called The Counter Intelligence Program – that made Americans demand investigation and reform of the FBI. Until the mid-1970s, there had never been oversight of the FBI and little coverage of the FBI by journalists, except for laudatory stories.A video chronicle about the 1971 break-in at an FBI office in Media, Pa., that uncovered vast FBI abuses.

‘Almost beyond belief’

The COINTELPRO operations ranged from crude to cruel to murderous.

Antiwar activists were given oranges injected with powerful laxatives. Agents hired prostitutes known to have venereal disease to infect campus antiwar leaders.

Many of the COINTELPRO operations were almost beyond belief:

· The project conducted against the entire University of California system lasted more than 30 years. Hundreds of agents and informants were assigned in 1960 to spy on each of Berkeley’s 5,365 faculty members by reading their mail, observing them and searching for derogatory information – “illicit love affairs, homosexuality, sexual perversion, excessive drinking, other instances of conduct reflecting mental instability.”

· An informant trained to give perjured testimony led to the murder conviction of Black Panther Geronimo Pratt, a decorated Vietnam War veteran. He served 27 years in prison for a murder he did not commit. He was exonerated in 1997 when a judge found that the FBI concealed evidence that would have proved Pratt’s innocence.

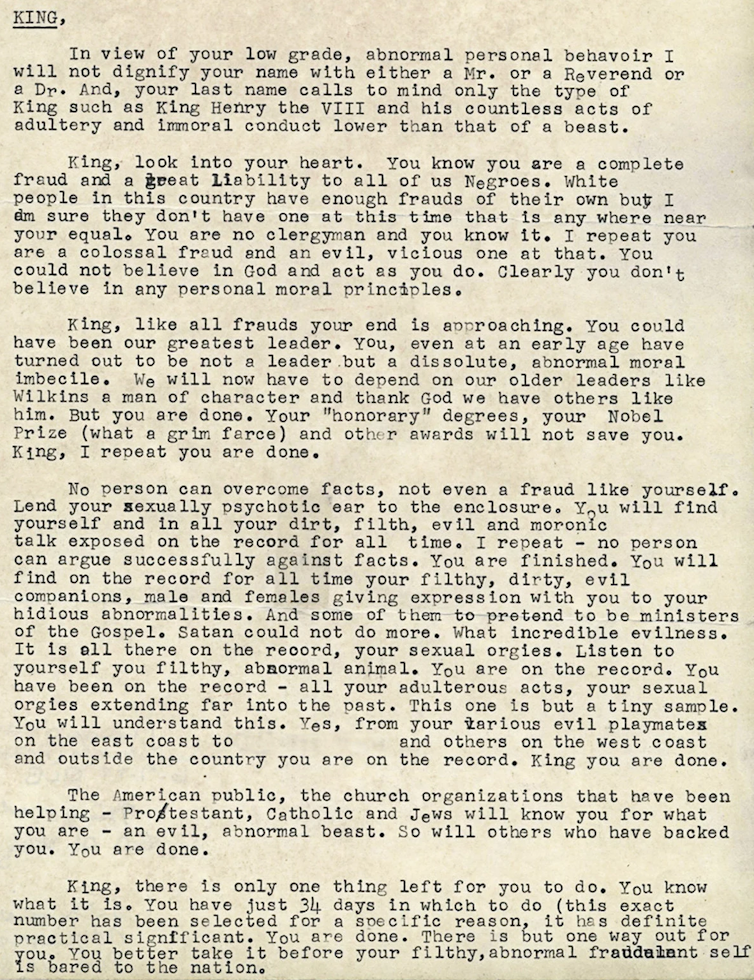

· The bureau spied for years on Martin Luther King Jr. After it was announced King would receive the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize, Hoover approved a particularly sinister plan that was designed to cause King to commit suicide.

· What one historian called Hoover’s “savage hatred” of Black people led to the FBI’s worst operation, a collaboration with the Chicago police that resulted in the killing of Chicago Black Panther Fred Hampton, shot dead by police as he slept. An FBI informant had been hired to ingratiate himself with Hampton. He came to know Hampton and the apartment very well. He drew a map of the apartment for the police on which he located “Fred’s bed.” After the killing, Hoover thanked the informant for his role in this successful operation. Enclosed in his letter was a cash bonus.

· Actress Jean Seberg was the victim of a 1970 COINTELPRO operation. In a memo, Hoover wrote that she had donated to the Panthers and “should be neutralized.” Seberg was pregnant, and the plot, approved personally by Hoover – as many COINTELPRO plots were – called for the FBI to tell a gossip columnist that a Black Panther was the father. Agents gave the false rumor to a Los Angeles Times gossip columnist. Without using Seberg’s name, the columnist’s story made it unmistakable that she was writing about Seberg. Three days later, Seberg gave birth prematurely to a stillborn white baby girl. Every year on the anniversary of her dead baby’s birth, Seberg attempted suicide. She succeeded in August 1979.

There was wide public interest in these revelations about COINTELPRO, many of which emerged in 1975 during hearings conducted by the Church Committee, the Senate committee chaired by Sen. Frank Church, an Idaho Democrat.

At this first-ever congressional investigation of the FBI and other intelligence agencies, former FBI officials testified under oath about bureau policies under Hoover.

One of them, William Sullivan, who had helped carry out the plots against King, was asked whether officials considered the legal and ethical issues involved in their operations. He responded:

“Never once did I hear anybody, including myself, raise the questions: ‘Is this course of action which we have agreed upon lawful? Is it legal? Is it ethical or moral?’ We never gave any thought to that line of questioning because we were just pragmatic. The one thing we were concerned about: will this course of action work, will it get us what we want.”

Ethical? Legal?

The future of the new FBI under Patel and Trump is unclear, especially in light of the president’s known tolerance for lawlessness, even violence. His gifts of clemency and pardons to Jan. 6 rioters are evidence of that.

As for Patel, fired FBI Officials stated in their recent lawsuit over those dismissals that Patel had told one of them it was “likely illegal” to fire agents because of the cases they had worked on, but that he was powerless to resist Trump’s demands.

The recent statements from both Trump and top aide Miller suggest the FBI’s independence, and broader constitutional requirements that the administration remain faithful to the law, are meaningless to them. They suggest that, like Hoover, they would criminalize dissent.

What will happen at the FBI after the internal purge ends? Will retribution fever wane? Will Patel refocus on the bureau’s chief mission, law enforcement? And will the questions asked in Congress in 1975, as the bureau was being forced to reject Hoover’s worst practices, be asked now: Is what we are doing ethical? Is it legal?

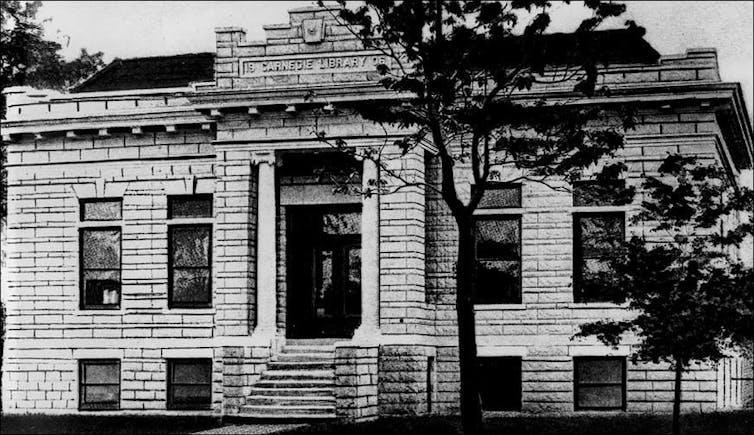

The Girard, Kansas Carnegie library.

The Girard, Kansas Carnegie library.