By Randall Hill

Terry Tillman, a 23-year-old black man, who was shopping at the Galleria Mall was killed by a Richmond Heights Police after receiving a call about a man carrying a concealed firearm.

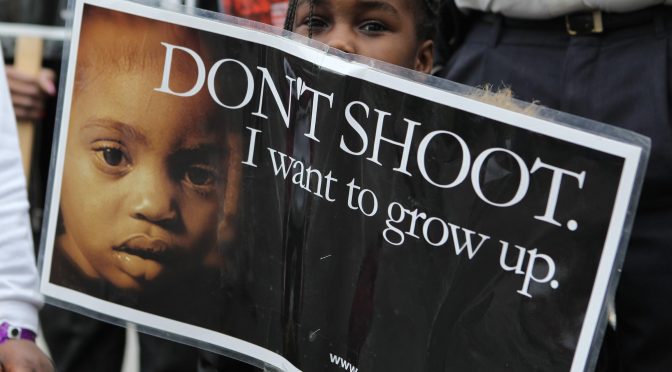

I have two sons who are 20 and 26 years old. Mr. Tillman could just as easily be one of my sons if they decide to exercise their constitutional right to carry a concealed weapon. I want my sons to have the ability to exercise their rights without the fear of being executed. They are both law-abiding citizens who shouldn't be considered criminals because they happen to be black. A gun provides some protection against violent criminals, but when black people encounter criminal, fearful or racist police officers there is little to no defense.

White men aren't targeted with suspicion when they exercise their gun rights even though mass shooters who target random victims are more likely to white men.

Legal behavior

The Galleria Mall has signs posted restricting guns, however, as we mention on our "Gun Law in Missouri" page, carrying a gun inside the Galleria was not illegal. A person who carries a concealed weapon onto restricted property and refuses to leave when asked may be removed from the premises by law enforcement officers and fined, as provided in Section 571.107 RSMo, but not charged with a crime unless an additional illegal act is committed on the private property.

Reports say that Mr. Tillman ran when asked about the gun, but running is not a crime. On June 5, 2019, a Federal Appeals Court ruled police who got a tip that a black man was carrying a gun had no authority to chase him down when he fled, and then to search him — at least in a state where carrying firearms is legal, US v. Brown, 925 F. 3d 1150 – Ct of Appeals, 9th Circuit 2019. The court in its opinion quoted Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens who said in a 2000 case:

“Among some citizens, particularly minorities and those residing in high-crime areas, there is … the possibility that the fleeing person is entirely innocent, but, with or without justification, believes that contact with the police can itself be dangerous.”

It is not illegal to run from a cop who has not detained you or has not issued an order to you. "If you can walk away, you can run away. It shouldn't matter the speed at which you move away." – Ezekiel Edwards, ACLU. However, running may provide reasonable suspicion depending on the circumstances. It IS illegal to run from a cop who has detained you or issued a lawful order. The order "STOP" is a lawful order, and from that point on, you are committing a crime if you do not stop.

The U.S. Supreme Court held in Tennessee v. Garner, 471 U.S. 1 (1985) that, under the Fourth Amendment, when a law enforcement officer is pursuing a fleeing suspect, the officer may not use deadly force to prevent escape unless "the officer has probable cause to believe that the suspect poses a significant threat of death or serious physical injury to the officer or others."

St. Louis County Police Sgt. Ben Granda provides limited information about the killing of Terry Tillman. The officer approached Mr. Tillman and allegedly advised him of the Galleria’s Zero Tolerance Policy on guns. The officer claims that as he was speaking with Tillman, he suddenly ran away. Sgt. Granda does not indicate that Mr. Tillman did anything illegal.

Felon in Possession and Warrant

I did not know Terry Tillman, so I am not personally familiar with his background or criminal history. I did visit his Facebook page, which includes some questionable post, but I attribute that to inexperience and youth; his page also indicated he was involved in music like my youngest son. Tillman was a rapper and probably felt the need to carry a gun for his own protection.

Tupac talked about gun possession and violence in a 1994 BET interview where he explained why so many young people carried guns.

A cursory check of Missouri Casenet indicates that Mr. Tillman had an active pending criminal case for felony theft, but had not yet been convicted. According to the docket entries, Mr. Tillman failed to appear in court and a bench warrant was issued.

Casenet also indicated other criminal charges and convictions, therefore, if those docket entries were correct, Mr. Tillman was a felon in possession of a firearm. However, the police officer would have had no prior knowledge of those facts and therefore his actions may not have been justified. Because of abuses within the criminal justice system, criminal histories may not tell the full story, consider the lesson from "When They See Us". Many people accept plea bargains and confess to crimes not because they are guilty but from fear of long prison sentences in an unfair criminal court system or to simply to be released from jail because they could not afford bail.

What if

What if Mr. Tillman did not have a prior felony conviction, but was still facing felony charges? Since he had not yet been convicted, he would not have been a felon and his gun rights should not have been restricted. Until the police know otherwise, that's the assumption Mr. Tillman should have been given, especially in light of the recent US v. Brown decision.

Does a bench warrant make you a fugitive from justice and thereby ineligible per RSMo 571.070? A Missouri Court of Appeals decision, Missouri vs. Chase, 490 SW 3d 771 (2016) indicates it does not. The court determined the phrase "fugitive from justice" was not defined and was ambiguous. Therefore, even a person with an active bench warrant with no prior felony convictions based on that court opinion retains the right to conceal carry.

Identification

It's unclear whether any Galleria Official or store employee requested that Mr. Tillman leave the premises. It's also unclear if there was a duty to make such a request before calling the police. The answers to those question might determine if Mr. Tillman would have even been required to identify himself to police.

The Richmond Heights Police had no way of knowing about a bench warrant or even who Mr. Tillman was. They can't assume just because he was black and had a gun in a permitless carry state that he was suspicious.

If there is no reasonable suspicion that a crime has been committed, is being committed, or is about to be committed, an individual is not required to provide identification, even in "Stop and ID" states. Kansas City is the only place in Missouri with a "Stop and identify" statute, RSMo 84.710(2). "Stop and identify" statutes authorize police to legally demand the identity of someone whom they reasonably suspect of having committed a crime.

If the police could not legally force Terry Tillman to identify himself, they couldn't have known he had an active warrant and would not have had grounds to arrest him.

Conclusion

The gun-rights of black people are under attack. Because of the no gun policy and signage, the police were within their rights to approach Mr. Tillman and inform him of the Gallerias no tolerance policy regarding weapons. When Mr. Tillman ran, he removed himself from the premises which complied with the newly provided information.

No one knows why Terry Tillman ran. Did he feel threatened or in danger? Did he fear arrest? But we do know that Mr. Tillman cannot explain his actions because he was killed. Running may not have been his best option, but people don't always behave rationally when they are in fear. The only person who can explain their actions is the officers that shot and killed Terry Tillman.

Was it reasonable for the police to be suspicious because Mr. Tillman ran? Probably, but an explanation about why deadly force was used should have been provided within minutes or hours at the utmost. It's been three days since Mr. Tillman was killed and we still don't know why deadly force was used.

Without reasonable suspicion that a crime is being committed, a black person who conceals carry should simply be viewed as exercising their constitutional rights, to behave otherwise is a constitutional violation. It's very possible that Mr. Tillman's Missouri and Federal constitutional rights were violated. Unless police reasonably feared for their safety or the safety of others, deadly force should not have been used.

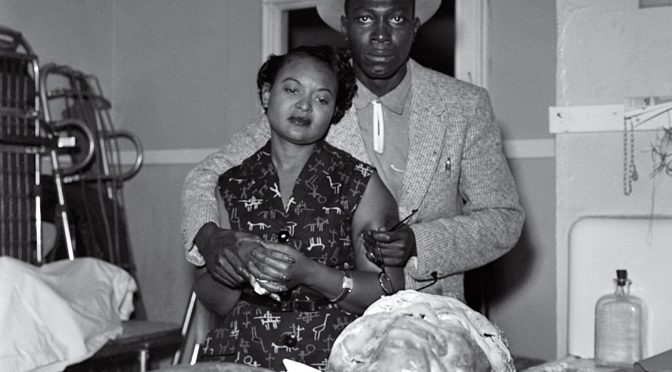

Family and friends of Mr. Tillman participated in a peaceful protest at the Galleria which resulted in arrests being made. Reportedly the family doesn't know where or how many times Terry Tillman was shot.

It should not be necessary to protest simply to get answers about why your child was killed. It's unreasonable that a family should be expected to accept the death of their loved one without a reasonable explanation. Transparency is required and expected and when not provide suspicion arises.

Certainly, there are plenty of cameras in and around the Galleria, the bank where the killing took place, and surrounding businesses. The public has a right to know whether body camera, dashcam, or other videos exist.

Based on past history, I expect the police to implement their no snitch policy (blue wall of silence) and to use the facts that Mr. Tillman had prior convictions, a pending felony charge, a bench warrant, a gun in his possession and that he ran as justification for their actions. The police had no prior notice about Mr. Tillman's convictions, charges or warrant, so those aren't valid reasons to chase and then shoot him. Since they have remained silent, I can only conclude the most obvious reason, "black man with a gun".

My heart goes out to the family and friend of Terry Tillman, I'm so sorry for your loss. As you encounter and hear from ignorant and hate-filled people trying to demoralize your spirits and denigrate the memory and legacy of Terry, remember there are so many others who are praying for you and grieving with you.