by Jasmine Harris, Ursinus College

Mikey Williams, one of the nation’s best 15-year-old basketball players, sent shockwaves through the sports world when he tweeted that he might go to a historically black college or university, also known as an HBCU. Here, Jasmine Harris, a researcher who studies student-athletes, elaborates on why Williams’ potential decision is generating so much interest.

1. What’s the big deal?

There is a lot of money at stake. Before he became an NBA star, Zion Williamson was worth an estimated US$5 million per year for Duke University. That figure is based on media exposure, marketing deals and ticket sales.

Williamson is not unique. Many a college sports star have made a lot of money for their college. Convincing a talented high school player to commit to a particular school is one of the most critical aspects of recruitment. A star player can help a school generate lots of revenue and expand their sports program. This is why I believe that college sports programs are more like businesses than part of a school.

HBCUs are historically underfunded. For that reason, HBCUs can’t recruit as competitively as some of their Division I peers. Without the funds to build programs and modern facilities capable to showcase star players in their quest to go pro, HBCUs are unlikely landing spots for the country’s most talented student athletes.

When HBCUs can’t attract the best young players, they miss out on the larger shares of NCAA revenue they could get from televised games, March Madness tournament participation and apparel and ticket sales. An HBCU has never won an NCAA national championship in football or men’s basketball. Instead, HBCUs compete in their own championship tournaments for the semi-segregated Mid-Eastern Atlantic Conference (MEAC) and Southwestern Atlantic Conference (SWAC). One player may not change the entire system, but one player can make a big difference for an individual school.

2. Is there anything special about the timing?

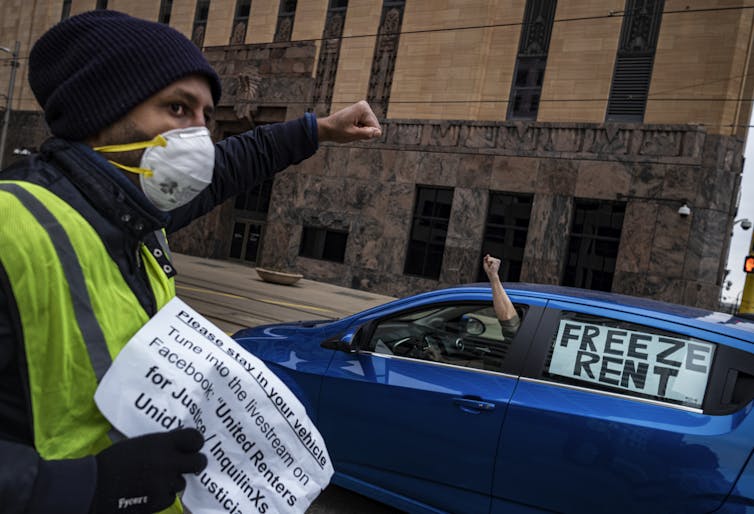

The convergence of increased discontent regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, news coverage of videos that show the killing of George Floyd at the hands of police, and the persistence of racist rhetoric, has created a perfect storm to re-envision which college a young black student should choose. College men’s basketball teams are made up of 56% black players student-athletes, but only about half of those athletes graduate from college after six years, in some cases that number is well below 50%. Less than 2% will be drafted into professional leagues.

These are black kids who are grappling in real time with their own racial identities, their place in the social hierarchy, and the systemic disadvantages of race in the U.S.

As the NCAA tries to maintain institutional status quo where student-athletes are prevented from being paid for sports participation, while players advocate for their right to generate their own revenue, black student-athletes like Williams are recognizing their role in the financial health of the schools for which they choose to play. As Williams stated on Instagram, “WE ARE THE REASON THAT THESE SCHOOLS HAVE SUCH BIG NAMES AND SUCH GOOD HISTORY … But in the end what do we get out of it?”

Committing to play for an HBCU isn’t just a neutral, short-term decision in this case. The potential for change instigated as a result of a top player rejecting a predominantly white college in favor of an HBCU is particularly significant, specifically in 2020 as black colleges struggle to stay afloat, but also more possible than ever.

3. Can just one player shake things up?

In the short term, probably not. However, Williams has the potential to influence other players in the future – and that may be more important. Colleges and universities depend heavily on revenue from men’s basketball and football games to maintain stable operating budgets across the entire institution. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed how precarious the financial relationship is between sports and Division I programs. Forfeiting 2020 revenue means these schools will have even thinner margins, and reduced budgets in the years immediately after the pandemic. This will create greater opportunity for a reorganization of the Division I sports hierarchy.

If Williams were to attend an HBCU, his presence would immediately improve the school’s bargaining position for television contracts and marketing deals. It could also lead to an increase in ticket sales and attract additional potential star players.

His decision could ultimately change how star high school athletes choose which college to attend. And if more choose HBCUs, these players have the power to shift a longstanding system which benefits predominantly white schools, to one where black colleges can become more competitive in sports.

Republished with permission under license from The Conversation.