The 1811 German Coast uprising was a revolt of black slaves in parts of the Territory of Orleans. The revolt began on January 8, 1811, at the Andry plantation. After striking and badly wounding Manuel Andry, the slaves killed his son Gilbert. The uprising occurred on the east bank of the Mississippi River in what is now St. John the Baptist, St. Charles and Jefferson Parishes, Louisiana.

The rebellion gained momentum quickly. The 15 or so slaves at Andry's plantation, about 30 miles upriver from New Orleans, joined another eight slaves from the next-door plantation of the widows of Jacques and Georges Deslondes. This was the home plantation of Charles Deslondes, a slave driver (overseer who was himself enslaved) later described by one of the captured slaves as the "principal chief of the brigands."

Between 64 and 125 enslaved men marched from sugar plantations in and near present-day LaPlace on the German Coast toward the city of New Orleans, LA. They collected more men along the way. Some accounts claimed a total of 200 to 500 slaves participated. During their two-day, twenty-mile march, the men burned five plantation houses (three completely), several sugarhouses, and crops. They were armed mostly with hand tools.

At the plantation of James Brown, Kook, one of the most active participants and key figures in the story of the uprising, joined the insurrection. At the next plantation down, Kook attacked and killed François Trépagnier with an axe. He was the second and last planter killed in the rebellion. After the band of slaves passed the LaBranche plantation, they stopped at the home of the local doctor. Finding the doctor gone, Kook set his house on fire.

Some planters testified at the trials in parish courts that they were warned by their slaves of the uprising. Others regularly stayed in New Orleans, where many had town houses, and trusted their plantations to overseers to run. Planters quickly crossed the Mississippi River to escape the insurrection and to raise a militia.

As the slave party moved downriver, they passed larger plantations, from which many slaves joined them. Numerous slaves joined the insurrection from the Meuillion plantation, the largest and wealthiest plantation on the German Coast. The rebels laid waste to Meuillion's house. They tried to set it on fire, but a slave named Bazile fought the fire and saved the house.

After nightfall the slaves reached Cannes-Brulées, about 15 miles northwest of New Orleans. The men had traveled between 14 and 22 miles, a march that probably took them seven to ten hours. By some accounts, they numbered "some 200 slaves," although other accounts estimated up to 500. As typical of revolts of most classes, free or slave, the insurgent slaves were mostly young men between the ages of 20 and 30. They represented primarily lower-skilled occupations on the sugar plantations, where slaves labored in difficult conditions with a low life expectancy.

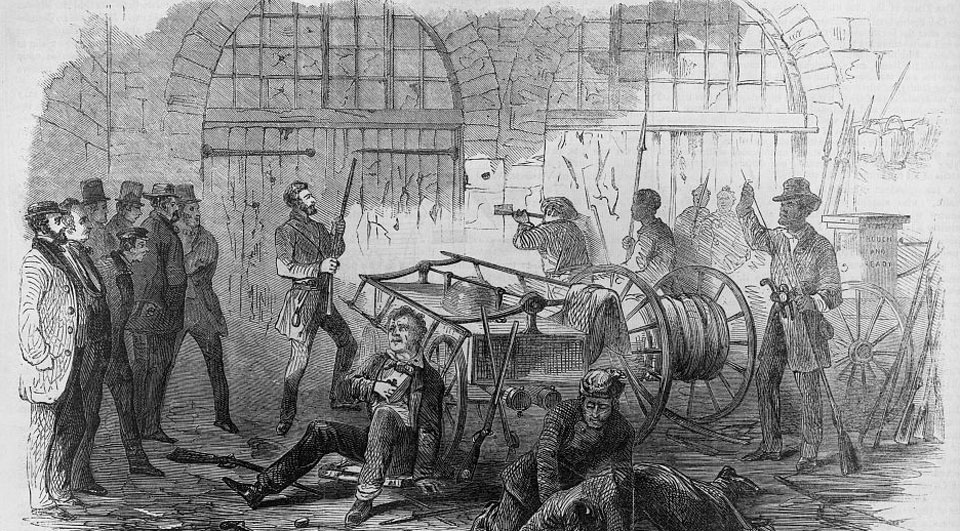

Despite his axe-wound, Col. Andry crossed the river to contact other planters and round up a militia, which pursued the rebel slaves. By noon on January 9, people in New Orleans had heard about the German Coast insurrection. By sunset, General Wade Hampton I, Commodore John Shaw, and Governor William C.C. Claiborne sent two companies of volunteer militia, 30 regular troops, and a detachment of 40 seamen to fight the slaves. By about 4 a.m. on January 10, the New Orleans forces had reached Jacques Fortier's plantation, where Hampton thought the escaped slaves had encamped overnight.

However, the escaped slaves had started back upriver about two hours before, traveled about 15 miles back up the coast and neared Bernard Bernoudy's plantation. There, planter Charles Perret, under the command of the badly injured Andry and in cooperation with Judge St. Martin, had assembled a militia of about 80 men from the river's opposite side. At about 9 o'clock, this local militia discovered slaves moving toward high ground on Bernoudy's plantation. Perret ordered his militia to attack the rebel slaves, which he later wrote numbered about 200 men, about half on horseback. (Most accounts said only the leaders were mounted, and historians believe it unlikely the slaves could have gathered so many mounts.) Within a half-hour, 40 to 45 slaves had been killed; the remainder slipped away into the woods and swamps. Perret and Andry's militia tried to pursue them despite the difficult terrain.

On January 11, militia, assisted by Native American trackers as well as hunting dogs, captured Charles Deslondes, whom Andry considered "the principal leader of the bandits." A slave driver and son of a white man and a slave, Deslondes received no trial or interrogation. Samuel Hambleton described his execution as having his hands chopped off, "then shot in one thigh & then the other, until they were both broken – then shot in the Body and before he had expired was put into a bundle of straw and roasted!" His cries under the torture could intimidate other escaped slaves in the marshes. The following day Pierre Griffee and Hans Wimprenn, who were thought the murderers of M. Thomassin and M. François Trépagnier, were captured, killed, and their heads hacked off for delivery to the Andry estate. Major Milton and the dragoons from Baton Rouge arrived and provided support for the militia, since Governor Hampton believed them supported by the Spanish in West Florida.

Having suppressed the insurrection, the planters and government officials continued to search for slaves who had escaped. Those captured later were interrogated and jailed before trials. Officials convened three tribunals: one at Destrehan Plantation owned by Jean Noël Destréhan in (St. Charles Parish), one in St. John the Baptist Parish, and the third in New Orleans (Orleans Parish).

The Destrehan trials, overseen by Judge Pierre Bauchet St. Martin, resulted in the execution of 18 of 21 accused slaves by firing squad. Some slaves testified against others, but others refused to testify nor submit to the all-planter tribunal. The New Orleans trials resulted in the conviction and summary executions of 11 more slaves. Three were publicly hanged in the Place d'Armes, now Jackson Square. One of those spared was a thirteen-year-old boy, who was ordered to witness another slave's death and then received 30 lashes. Another slave was treated with leniency because his uncle turned him in and begged for mercy. The sentence of a third slave was commuted because of the valuable information he had given.

The heads of the executed were put on pikes, and the mutilated bodies of dead rebels displayed to intimidate other slaves. By the end of January, nearly 100 heads were displayed on the levee from the Place d'Armes in central New Orleans along the River Road to the plantation district and Andry's plantation.

While the slave insurgency was the largest in US history, the rebels killed only two white men. Confrontations with militia and executions after trial killed 95 black people.